Discover Iran: Hormozgan’s architecture, where climate ingenuity meets maritime heritage

By Ivan Kesic

- The historical mosques of Hormozgan universally forgo the iconic domes of Iranian architecture in favor of the shabestan-iwan model, a design where a dense, columned hall provides a naturally cool, ventilated refuge from the coastal heat, demonstrating a form perfectly tailored to environmental necessity over imperial aesthetics.

- The strategic importance of the Persian Gulf is physically etched into the landscape through formidable structures like the Portuguese castles on Hormuz and Qeshm islands, whose massive 16th-century walls and secret escape tunnels narrate a century of colonial ambition before their decisive liberation by Safavid forces in 1623.

- The region's traditional ab-anbars are sophisticated feats of passive engineering, featuring partially subterranean, domed reservoirs made with special waterproof mortar (saruj) and integrated with social spaces called tey takh, representing a pious response to water scarcity that transformed sporadic rainfall into a sustainable public resource.

Iran’s southern province of Hormozgan, shaped by the stark contrast between sun-scorched desert and the brilliant blue of the Persian Gulf, preserves a remarkable history not through grand imperial monuments, but through the finely adapted architecture of everyday life.

From the soft, cooling breezes channeled through its coastal mosques to the stern fortifications guarding its rocky shores, and the life-sustaining domes of its desert water reservoirs, the architecture of Hormozgan tells a compelling story of adaptation, resilience, and cultural identity.

Long a crossroads of maritime trade and overland caravan routes, the region developed distinctive building traditions that responded directly to its harsh climate, strategic position, and communal needs.

The province’s architectural heritage can be understood as a triad of ingenious solutions: religious spaces shaped for climatic comfort, military and commercial structures designed for defense and connectivity, and hydraulic engineering feats essential for survival.

Together, the coastal mosques, the network of castles and caravanserais, and the ubiquitous ab-anbars stand as an integrated testament to how the people of southern Iran flourished by creating a harmonious, pragmatic, and deeply localized built environment.

Coastal mosques of Hormozgan

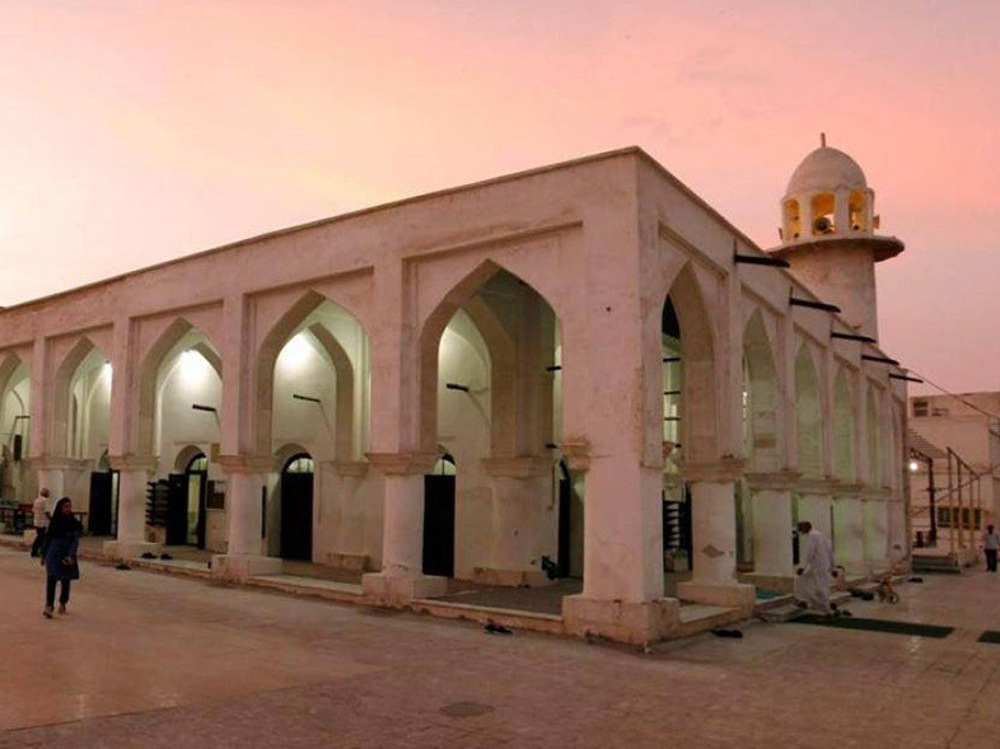

Along the sun-baked coast of Iran's Hormozgan province, facing the shimmering waters of the Persian Gulf, a collection of historical mosques offers a unique architectural story.

Unlike the grand, domed masterpieces of Isfahan or the intricate four-iwan courtyards of Shiraz, these mosques represent a distinct, localized architectural language.

Built primarily over the last three centuries, their forms were shaped not by imperial decree, but by a profound dialogue with a challenging environment, a relentless hot and humid climate, limited local materials, and the cultural influences of a major maritime crossroads.

These structures can be understood through seven key criteria: their physical features, decorative schemes, plan form, courtyard configuration, the critical orientation of the qibla (direction of prayer) and mihrab (prayer niche), the form of their entrances, and the relationship of that entrance to the mihrab.

The result is a fascinating regional typology that prioritizes pragmatic adaptation and community function over monumental grandeur, showcasing how Islamic architecture ingeniously localized itself on Iran's southern shores.

The most immediate and defining characteristic of Hormozgan's historical mosques is their almost universal reliance on the shabestan-iwan model.

The shabestan, a hypostyle hall with rows of columns supporting a flat or vaulted roof, is the absolute heart of these structures. This design is a direct and brilliant response to the climate.

The dense forest of columns and thick walls creates a cool, shaded interior refuge from the oppressive coastal heat, fostering a natural ventilation that a large, open dome would not allow.

Distinguishing them from iconic Iranian architecture, these coastal mosques are characterized by a notable absence of the dome, favoring instead flat or vaulted roofs.

Attached to this shabestan is often an iwan, a large, vaulted portal or terrace open on one side. This iwan functions as an intermediary, a shaded space for congregation and socializing, further extending the cool, layered transition from the blazing exterior to the serene interior.

This configuration, seen in mosques like the beautiful Bandar Lengeh's Malek ibn Abbas Mosque from the Safavid era, demonstrates a form perfectly tailored to environmental necessity.

This architectural adaptation extends to the mosques' spatial organization and orientation. While grand central courtyards (sahn) are a hallmark of Iranian mosque design, a closer look at Hormozgan's mosques reveals a more flexible and context-driven approach.

Courtyards do exist, but they are not always the central, symmetrical focal point.

They frequently appear on the eastern side of the building, and sometimes on the northern or southern sides, suggesting their placement was dictated more by urban plot layout, prevailing winds for cooling, and the creation of shaded outdoor space rather than a rigid axial plan.

Similarly, the alignment of the qibla, toward Mecca, is paramount. While mosques are built on an east-west axis for prayer, their overall siting within the urban fabric often prioritizes integration into the existing cityscape over a strict cardinal orientation.

This pragmatic flexibility underscores the mosques' role as organic, daily parts of the community rather than imposed monumental landmarks.

The entrance to these mosques is another element of both social and spatial significance. These historical mosques consistently feature defined, separate entrances for men and women, a design element that speaks to social structures and ensures functional privacy for all worshippers.

The relationship between this entrance and the mihrab inside is a carefully considered spatial sequence, guiding the visitor from the public street into the spiritual focus of the prayer hall.

While the exteriors are often modest, the interiors reveal a localized decorative charm. Grand tilework is rare, replaced by intricate plaster decorations (gach-bori) featuring Islamic motifs, floral patterns (buta), and intricate geometric designs.

Columns are often embellished with molded plaster bricks, and muqarnas (stalactite vaulting) appears in more elaborate examples like the Malek ibn Abbas Mosque.

These decorations, while beautiful, are typically modest in scale, emphasizing an aesthetic of refined simplicity suited to the local environment and resources.

The historical context of Hormozgan as a bustling maritime gateway is subtly imprinted on these structures. The province was a point of contact between Iran and the wider world—Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Indian subcontinent.

This confluence of cultures, arriving with traders and sailors, inevitably influenced local aesthetics and techniques, contributing to a unique regional blend not found in the inland empires.

The Hormozgan's historical mosques, from the Safavid-era Malek ibn Abbas to Qajar-period gems like the Galehdari Mosque in Bandar Abbas and the Pahlavi-era Karchi Mosque, represent a continuous, evolving vernacular tradition.

They were built by and for local communities, using local materials like plaster, stone, and clay to solve local problems of climate and space.

Those mosques stand as a testament to the ingenious and adaptive spirit of regional Iranian architecture. They forgo the soaring domes and vast courtyards of their famous counterparts to master a different set of priorities: creating cool, communal sanctuaries in a harsh climate.

Through their dominant shabestan-iwan plans, context-sensitive courtyards, pragmatic orientations, separate entrances, and delicate plasterwork, they articulate a coastal Islamic identity.

They are not monuments to imperial power, but rather architectural embodiments of daily faith and community resilience, offering a profound and beautiful lesson in how universal forms beautifully localize, shaped by the sun, the sea, and the needs of the people who gather within their walls.

Hormozgan's castles and caravanserais

The coastal province of Hormozgan holds a silent, stone-built chronicle of its tumultuous history, not in grand imperial palaces but in a dramatic network of castles and caravanserais that dot its rugged landscape from the mountainous interior to its strategic islands.

These fortifications, ranging from formidable Portuguese colonial outposts to ingenious local mountain strongholds, narrate a 500-year saga of maritime empire, fierce local resistance, and the vital caravan trade that once pulsed through this arid region.

Their ruins, perched on remote cliffs and overlooking the turquoise waters of the Persian Gulf, stand as enduring monuments to a past shaped by global power struggles and the resilient communities who defended their land.

The most iconic chapters of this story are written in the formidable stone of the Portuguese Castles on the islands of Hormuz and Qeshm, constructed in the early 16th century when the Portuguese navigator Alfonso de Albuquerque sought to dominate the maritime trade route between India and Europe.

The irregular polygonal fortress on Hormuz Island, with its massive walls 3.5 meters thick and 12-meter-high towers, was a statement of colonial power, equipped with weapons depots, a church, and a sophisticated water reservoir.

Similarly, the fortress on Qeshm Island, built from coral stone and gypsum mortar, featured four corner towers and a sprawling layout designed for long-term occupation, complete with a secret three-kilometer escape tunnel discovered as late as 2008, leading from the castle to the heart of Qeshm city.

The Portuguese occupation lasted for over a century, but their dominance was decisively shattered in 1623 when the Safavid general Imam Qoli Khan, under Shah Abbas I, liberated both strongholds in a celebrated reassertion of Iranian sovereignty, events still commemorated as symbols of national resistance against foreign arrogance.

Beyond these coastal sentinels, the inland castles reveal a different, deeply localized narrative of defense and governance.

Scattered across the province's mountainous regions, castles like Gohran in Bashagard and Kamiz near Rudan were built by and for local khans and communities.

Gohran Castle, a Qajar-era fortress, is a masterpiece of pragmatic defense, constructed atop a hill with three sheer cliff faces and a single accessible side protected by a 60-meter-deep moat.

Its most astonishing feature was a well dug over 200 meters down to a river, securing a permanent water supply during sieges.

Kamiz Castle, dating from the Safavid to Qajar periods, served as a strategic lookout, its guards monitoring all movement in the Siba region from its high mountain peak and reporting directly to the regional ruler.

These structures, built with simple yet effective materials like mud, stone, and molded brick, were not seats of empire but refuges for local populations, their design perfectly adapted to the harsh terrain.

Similarly, Hazareh Castle (also known as Bibi Minu Castle) in Minab functioned as the center of local government until the late Qajar period, protected by a moat and a permanent garrison of 100 soldiers.

The local folklore attributes its construction to two legendary sisters, Bibi Minu and Bibi Nazanin, weaving myth into the fabric of its history.

Complementing these military installations were the vital nodes of commerce and travel: the caravanserais.

These roadside inns, such as the Bastak Caravanserai on the historic route from Lar to Bandar Lengeh, provided shelter, security, and stables for the caravans that moved goods and people across the arid landscape.

Built with stone, plaster, and mortar around a central courtyard, they were hubs of economic and social exchange.

While many now lie in picturesque ruins, their remains powerfully evoke the bustling activity of merchants, porters, and travelers who sustained the region's connection to wider networks.

Together, this ensemble of castles and caravanserais forms an indispensable historical tapestry.

From the colonial ambitions etched into the walls of the Portuguese forts to the resilient, community-focused architecture of the mountain castles and the commercial lifeblood that flowed through the caravanserais, these structures are far more than silent ruins.

They are the physical narrators of Hormozgan's identity, bearing witness to its role as a contested gateway to the world and the enduring spirit of its inhabitants who built, defended, and traversed this storied land.

Enduring legacy of Hormozgan's ab-anbars

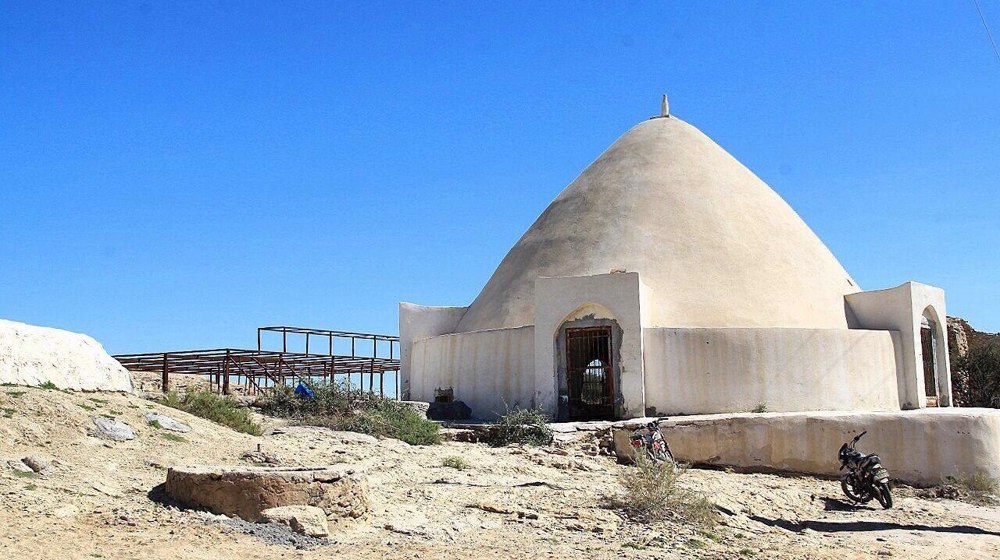

Scattered across arid landscapes of Iran's Hormozgan province are structures of profound ingenuity and cultural resonance: the traditional ab-anbar, or water reservoir.

These are not mere pits for holding water but sophisticated feats of vernacular architecture, born from an intimate dialogue with a merciless climate and refined over centuries into elegant, domed cisterns that represent a pinnacle of community-driven environmental adaptation.

In a region where the northern shores of the Persian Gulf are defined by high temperatures and scarce, unpredictable rainfall, the capture and preservation of every drop of rainwater was, for generations, a matter of survival.

The ab-anbar stands as the brilliant answer to this challenge, a symbol of harmony with nature that transformed sporadic seasonal showers into a lifeline for settlements far from reliable rivers or springs.

Their design is a masterclass in passive engineering, strategically placed within natural runoff channels to intercept precious water.

To combat the intense heat and evaporation, they were built partially subterranean, with their most distinctive feature being the beautiful, often whitewashed dome that crowns the reservoir.

This dome, constructed from local stone, brick, and a special waterproof mortar called saruj, serves the critical dual purpose of shielding the water from contamination and the scorching sun while keeping it remarkably cool.

The construction of an ab-anbar was a deeply altruistic act, considered a pious deed of the highest social merit, comparable in virtue to building a mosque.

A single ab-anbar, often endowed as a charitable trust for public use, could sustain a neighborhood or an entire village. Its architecture extended beyond the simple tank to include an integrated system for water management and community life.

A network of small channels, known as mamr, would funnel rainwater from surrounding slopes into the central reservoir. Ingenious pre-filtering basins called dash dareh were built in the inlet path to capture silt and debris, protecting the water quality.

Perhaps most socially significant were the tey takh—cool, arched chambers or shaded platforms built adjacent to the reservoir.

These served as vital public spaces where travelers could find respite from the heat and neighbors could gather, transforming the utilitarian site of water collection into a hub of social interaction.

The water itself was drawn not by descending steps, as seen in northern Iranian ab-anbars, but by bucket and rope from an access portal, sometimes poetically called the "lion's mouth."

Historical evidence suggests the principles of rainwater harvesting here have ancient, possibly pre-Islamic, origins, with the form evolving into the recognizable domed structure over centuries.

Each ab-anbar was a unique project, its size and capacity directly reflecting the generosity of its benefactor and the needs of the community.

Examples like the Darya Dolat ab-anbar in Bandar Kong, with its impressive reservoir holding over 8,600 cubic meters of water, speak to ambitious civic projects.

Another fascinating variant is the Panj Ta (fivefold) ab-anbar near Bandar Lengeh, a late-Qajar era structure featuring a central circular tank surrounded by four rectangular arms, creating a complex and distinctive footprint.

While the advent of modern piped water systems has reduced daily reliance on these ancient reservoirs, they remain powerful landmarks on the Hormozgan landscape.

They are revered not as obsolete relics, but as timeless monuments to collective foresight, environmental intelligence, and social cohesion.

In their quiet, enduring presence, these domed ab-anbars tell a foundational story of human resilience, reminding us that in the heart of a desert, civilization was nurtured not just by water, but by the shared wisdom and communal spirit that knew precisely how to save it.

Iraq's former PM Maliki rejects ‘blatant US interference’ after Trump warning

Iran, Saudi Arabia warn of 'dangerous consequences' of regional escalation

VIDEO | India, EU seal trade pact slashing tariffs to curb US reliance

VIDEO | Israel’s continued violations undermine transition to 2nd phase of Gaza truce

As TikTok falls into Zionist hands, UpScrolled fills the vacuum to give voice to Palestine

Discover Iran: Hormozgan’s architecture, where climate ingenuity meets maritime heritage

From Monroe to Trump: Imperialist footprint behind President Maduro’s kidnapping

FM Araghchi: Negotiations cannot work under threats

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website