Discover Iran: Historical, natural, and economic tapestry of idyllic Hormozgan islands

By Ivan Kesic

- Kish Island has been transformed from an exclusive royal resort under the Pahlavi regime into Iran's primary free trade zone, creating a unique socio-economic experiment where duty-free shopping, international medical tourism, and luxury hospitality operate under a special legal framework aimed at bypassing Western-imposed sanctions and attracting foreign investment.

- The Iranian siege and capture of the Portuguese colonial fort on Qeshm Island in 1622 was a decisive event that directly led to the fall of the Portuguese Empire's stronghold at Hormuz, permanently shifting the center of Persian Gulf trade to Bandar Abbas and altering the regional balance of power.

- The tiny, arid island of Hormuz, celebrated for its vividly colored mineral soils and devoid of natural water, has served two historically monumental roles: first, as the wealthy medieval mercantile kingdom that controlled Indian Ocean trade, and second, as the modern-day strategic sentinel overlooking the Strait of Hormuz, through which a substantial portion of the world's global oil supply passes.

Beneath the relentless sun of the Persian Gulf, scattered along the strategic waterways of Hormozgan Province, lies an archipelago of Iranian islands, each a distinct gem woven into the nation’s rich tapestry of history, ecology, and economy.

From the vast, geologically dramatic landscapes of Qeshm to the glittering, modernized shores of Kish and the mineral-rich, historically pivotal isle of Hormuz, these islands have long served as ancient trading hubs, colonial battlegrounds, ecological sanctuaries, and engines of contemporary development.

Their stories are etched into coral-stone Portuguese forts, whispered in the Bandari dialect of coastal fishermen, and reflected in the glass façades of duty-free shopping malls, together forming an indispensable chapter in the narrative of Iran and the wider Persian Gulf.

This article traces deep historical currents, resilient natural environments, and ambitious economic transformations, revealing how lands once known to ancient geographers as Oaracta and Organa have emerged as the natural pearls of the Persian Gulf, balancing a precious heritage with the promises and pressures of the future.

Qeshm: The geopolitical stronghold and ecological sanctuary

Qeshm Island, the largest in the Persian Gulf, is a land where history is layered like its striated sedimentary cliffs, bearing witness to millennia of human ambition and the relentless forces of nature.

Known in antiquity as Abarkavan, or the “Island of Cows,” its elongated form running parallel to the mainland coast has long endowed it with exceptional strategic value, making it a perpetual object of desire.

Long before European powers turned their gaze toward the Persian Gulf, Qeshm functioned as a vital dependency of the medieval Kingdom of Hormuz, supplying precious fresh water to the arid island-capital and flourishing as a prosperous mercantile center. Its fate became inseparable from global power struggles in the early seventeenth century, when the Portuguese, seeking to pressure Safavid Iran and outmaneuver English rivals, constructed a formidable fort on the island in 1621. Built of sea coral and plaster, this fortress soon became the flashpoint for a decisive shift in regional control.

The ensuing siege, a joint operation led by Emam-Qoli Khan, resulted not only in the Portuguese surrender on Qeshm but also precipitated the fall of Hormuz itself in 1622, an event that fundamentally reoriented Persian Gulf trade toward Bandar Abbas.

Yet Qeshm’s trials did not end there. The island became a contested pawn in subsequent struggles involving Dutch interests, expanding Omani forces, and resurgent Iranian authorities. Local Arab sheikhs, most notably Rashid of Basidu, skillfully navigated these turbulent dynamics, carving out spheres of influence amid shifting allegiances.

In the nineteenth century, the British Indian Navy established a coaling station at Basidu, underscoring Qeshm’s enduring strategic importance within imperial maritime networks, a presence that persisted until Iran reasserted full control in the 1930s.

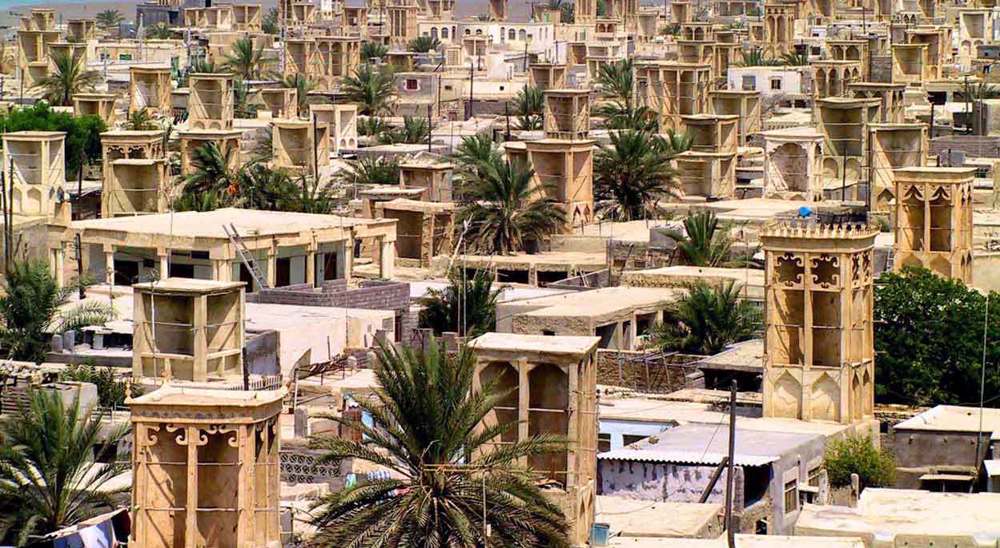

The island’s historical landscape is thus a palimpsest of successive eras, scattered with monuments that collectively narrate its complex past. The Portuguese Castle in Qeshm city and the so-called Nader Shahi Castle in Laft stand as rugged sentinels of colonial and Safavid military architecture.

The Barkh Mosque in the village of Kosheh, possibly dating to the early Islamic conquests and restored after a devastating fourteenth-century earthquake, attests to the deep-rooted spiritual life of the island’s inhabitants.

Equally revealing are the ingenious tala – or “gold” – wells of Laft, traditionally numbering 366, which exemplify ancient solutions to chronic water scarcity. The subterranean water reservoir at Kharbas hints at settlement patterns extending back to the Sassanid period, while the remnants of an English cemetery in Basidu and the charitable Bibi Ab Anbar, constructed in the early nineteenth century, complete a portrait of an island continuously shaped, adapted, and contested by successive waves of residents, rulers, and traders.

Yet Qeshm’s grandeur lies not only in its human history but also in its extraordinary natural architecture, a distinction recognized by its designation as a UNESCO Global Geopark.

The island is a vast open-air geological museum, where erosion, salt tectonics, and sedimentation have sculpted a surreal and ever-evolving landscape. The Valley of the Stars, with its towering, needle-like formations and the extensive networks of salt caves, including the mesmerizing Namakdan, the longest salt cave in the world, offers glimpses into the Earth’s subterranean artistry.

Along the coast, the Hara marine forests form one of the region’s most vital and fragile ecosystems. These expansive mangrove stands serve as nurseries for fish and crustaceans and as sanctuaries for migratory birds. Together with Qeshm’s coral reefs and sandy beaches frequented by nesting sea turtles, they underscore the island’s immense ecological significance.

For generations, the local economy has been intimately tied to this environment, sustained by fishing, small-scale agriculture, date cultivation, and, historically, pearl diving. The export of pure salt blocks and firewood once supplied markets across the Persian Gulf.

In the late twentieth century, recognizing Qeshm’s unique potential, the Iranian government established the Qeshm Free Area Authority in 1989. This initiative sought to leverage the island’s strategic location, nearby natural gas resources, and rich ecological and cultural heritage to develop a hub for trade, industry, and eco-tourism.

Today, Qeshm embodies a delicate and dynamic balance, striving to preserve its ancient geological wonders and traditional ways of life while navigating the demands of modern economic development. It stands as a colossal testament to the enduring interplay of nature and history at one of the world’s most enduring crossroads.

Kish: Duty-free mirage and engine of modern ambition

If Qeshm represents the raw, ancient soul of the Persian Gulf islands, Kish embodies their sleek, aspirational future, transformed from a quiet pearling outpost into Iran's premier showcase of economic liberalization and cosmopolitan tourism.

Kish's historical significance as a medieval mercantile powerhouse, then known as Qays, is often eclipsed by its contemporary glitter.

Between the 11th and 13th centuries, it rose to challenge Hormuz, its rulers, whether of Julanda or Buyid affiliation, commanding formidable fleets that dominated trade routes to India and East Africa and even launched an assault on Aden in 1135.

The ruins of the ancient city of Ḥarireh, strewn with Chinese porcelain, attest to its role in a vast network of Indian Ocean commerce, while its pearls were praised by travelers from Marco Polo to Abu’l-Feda.

This golden age waned after its conquest by Hormuz in the 13th century, and for centuries, Kish reverted to a modest existence of fishing and date cultivation, its population a fraction of its former eminence.

The modern metamorphosis of Kish Island stands as a testament to the isolation, corruption, and grotesque excess that defined the final decade of the Pahlavi dictatorship.

The island's transformation was not born of national development but of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s personal desire for a secluded luxury enclave, a project that deliberately severed the land from its own people.

Following a royal visit in 1969, the regime, spearheaded by court minister Asadollah Alam, embarked on a colossal mission to fabricate a “Persian Gulf Paradise” modeled on elite Western resorts.

With an estimated budget exceeding $100 million (over $800 million in today's value), a fortune drawn from the nation's oil wealth, the regime-backed Kish Development Organization, overseen by the Shah’s inner circle, set about constructing a world of private palaces, lavish guest villas, and five-star hotels staffed with French chefs and casinos.

This construction came at a direct and brutal human cost: native settlements like Mashhe and Sefin were forcibly evacuated, their inhabitants displaced to make way for a playground they were forbidden to enter.

The island was deliberately sealed off from the Iranian public, becoming a clandestine zone where the royal family, wealthy Arab sheikhs, and Western associates such as Nelson Rockefeller could indulge in unchecked extravagance, financial opacity, and, as contemporary accounts attest, rampant moral decay, all while shielded from national laws and judicial oversight.

This project was the physical embodiment of the Pahlavi regime’s deepening detachment.

As one memoir from within the court described, Kish operated as a private fiefdom where “everything that was done there… was entirely private,” enabling not only luxury but also “all kinds of illegal activities” without fear of prosecution.

The stark irony was immortalized by a pilot for the Shah’s family who, while enjoying “opulent no expense-spared” comforts on Kish in the late 1970s, reflected that his vacation coincided with Iranians “denied their fair share of the oil wealth” assembling in mass protest nationwide.

Kish was thus not merely a resort; it was a symbol of the dictatorship's priorities, a fortified island of privilege amid a sea of mounting popular discontent.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution abruptly ended this era of private plunder, leaving grandiose projects unfinished. After the Holy Defense war, the Islamic Republic resurrected the island’s infrastructure but inverted its fundamental purpose.

In 1989, the state revived Kish as the nation’s first Free Trade Zone under a new, people-oriented mandate.

The Kish Free Zone Organization repurposed the abandoned shells of royal ambition, transforming forbidden luxury hotels into public accommodations and the exclusive airport into an open gateway.

The legal framework was rewritten not to enable secrecy for the few but to attract investment and tourism for the many.

Today, the island, once a forbidden citadel for the dictator and his clique, welcomes approximately two million visitors annually, the vast majorityof Iranian families and citizens previously barred from their own shoreline.

With an average of 20,000 domestic and international flights each year, Kish now thrives as a public economic engine and popular destination, its history a powerful narrative of how national assets, once captured by a corrupt elite, can be reclaimed and repurposed for the society originally excluded.

Today, Kish is a study in contrasts and concentrated ambition. Its economy is a tripartite engine driven by shopping tourism, medical tourism, and leisure tourism.

As a duty-free zone, it has become a shopping destination for Iranians and regional visitors, with mammoth malls such as Pardis and Mica Mall offering international luxury goods and electronics at competitive prices, generating hundreds of millions in annual revenue.

Parallel to this, Kish has cultivated a medical tourism sector, marketing itself as a cost-effective destination for cosmetic surgery, dental care, and specialized procedures at facilities such as the JCI-accredited Kish International Hospital, drawing tens of thousands of patients annually from across the region.

The island's natural assets are packaged for leisure: Coral Beach for snorkeling, Dolphin Park for family entertainment, and luxury resorts like the overwater Toranj Marine Hotel cater to a growing domestic and international tourist flow, exceeding 2 million visitors annually.

Beneath this glossy surface, however, lies a complex socio-economic reality.

The island's rapid urbanization, marked by soaring skyscrapers and mega-projects, has strained its fragile ecosystem, contributing to coral reef degradation and placing immense pressure on water resources almost entirely supplied by energy-intensive desalination plants.

The governance structure is a distinctive hybrid, with the KFZO wielding vast economic autonomy alongside local municipal authorities.

While the FTZ has created employment, it has also attracted a large migrant workforce from mainland Iran and abroad.

Culturally, Kish presents a compelling amalgam: the local Bandari dialect, Arab-influenced traditions, and seafaring heritage persist in pockets, even as the dominant culture is shaped by consumerism, constant tourist influx, and the state’s regulatory framework.

Kish, therefore, stands as Iran's boldest experiment in globalized capitalism, a strategic asset for bypassing Western-imposed sanctions through trade and a social laboratory where tensions between preservation and development, tradition and modernity, and state control and economic freedom are enacted on a sun-drenched, coral-fringed stage.

Hormuz: The crimson jewel of the strategic strait

In stark contrast to the sprawling developmentalism of Kish, the tiny island of Hormuz is a place where history and geology assert themselves with unyielding force.

This barren, rocky outcrop guarding the eponymous strait is a landscape painted in vivid, almost surreal hues, deep reds, ochres, and yellows drawn from its rich deposits of iron oxide and ochre, earning it the evocative moniker “the Rainbow Island.”

Yet its significance far outweighs its physical scale, rooted in a location that has made it one of the most strategically coveted points on Earth for centuries.

The story of Hormuz is a tale of two cities. Old Hormuz, located on the Iranian mainland near Minab, was a prosperous port celebrated by early Islamic geographers for its sugarcane, dates, and commercial vitality. New Hormuz emerged in the early fourteenth century, when the population and royal court fled to the island under threat from Mongol incursions.

Though the move sacrificed access to freshwater and vegetation, it created an impregnable maritime entrepôt.

Under the Kingdom of Hormuz, the island became the linchpin of Indian Ocean commerce during the late medieval period, a vast emporium where, according to fifteenth-century accounts, merchants from Egypt, China, Java, and Venice converged. Its wealth, derived entirely from transshipment and trade, was legendary.

This prosperity inevitably attracted Portuguese ambition, and in 1515, Afonso de Albuquerque captured the island, erecting a formidable fort whose ruins still dominate Hormuz’s northern shore.

For more than a century, Portuguese Hormuz stood as the central pillar of the Estado da Índia, controlling access to the Persian Gulf and exacting tribute from passing commerce.

Its liberation in 1622 by the forces of Shah Abbas I marked a catastrophic blow to Portuguese imperial power and a decisive turning point that shifted Iran’s primary maritime outlet to nearby Bandar Abbas.

Thereafter, Hormuz entered a prolonged period of decline. Bereft of freshwater and eclipsed strategically, it receded into relative obscurity. Economic life contracted to fishing and the extraction of its vividly colored mineral soils, exported as pigments and ballast, while much of the population migrated seasonally to the mainland to escape the island’s searing summers.

In the modern era, Hormuz’s importance has been violently redefined by geopolitics and fossil fuels. The strait it overlooks has become the world’s most critical oil transit chokepoint, with roughly one-fifth of global oil consumption passing through its narrow waters.

This reality has returned Hormuz to the center of global strategic calculations. The island now hosts Iranian military installations as well, serving as both sentinel and potential lever in regional and international tensions.

Environmentally, Hormuz remains acutely fragile, its singular landscapes and surrounding marine ecosystems highly vulnerable. Efforts to cultivate a modest tourism sector, focused on its otherworldly geology, red-sand beaches, and the remnants of the Portuguese fortress, proceed cautiously, overshadowed by the island’s overwhelming military and strategic role.

Hormuz today thus stands as a potent symbol: a reminder of a glorious and ruthless mercantile past, a geological marvel of striking beauty, and a perpetual flashpoint in the high-stakes arena of global energy security, its crimson soil bearing silent witness to centuries of power struggles that continue to shape the world.

Constellation of lesser jewels: Larak, Hengam, and the guardians of tradition

Beyond the triumvirate of Qeshm, Kish, and Hormuz, the waters of Hormozgan are scattered with a constellation of smaller islands, each a distinct thread in the province’s rich tapestry, emphasizing natural resilience, historical depth, and traditional economies.

Islands such as Larak, Hengam, Abu Musa, and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs may lack the scale or headline-grabbing development of their larger neighbors, yet their significance is profound, rooted in ecology, heritage, and steadfast community life.

Larak Island, positioned in the strategic channel south of Hormuz, embodies a long history of settlement and defense. Its small, square Portuguese fort, possibly dating to the late sixteenth century, that once guarded vital freshwater sources for passing ships and kept watch over the strait.

Inhabited by the Ḏahuriyin people, whose Komzari dialect and cultural traditions closely link them to Oman’s Musandam Peninsula, Larak has preserved a distinct identity for centuries, sustained historically by fishing and, like many Persian Gulf islands, pearl diving.

Over time, its role expanded to include strategic functions: it hosted an oil transfer facility targeted during the Holy Defense war in the 1980s and today serves as a naval base. Ecologically, Larak remains vital, acting as a stopover for migratory birds such as flamingos, while its surrounding waters form part of the strait’s fragile marine ecosystem.

Hengam Island, southwest of Qeshm, presents a contrasting profile, increasingly oriented toward sustainable ecotourism. It is renowned for the daily spectacle of Persian Gulf bottlenose dolphins, observed through boat excursions from Qeshm.

The island also features striking geological formations, including sedimentary rainbow mountains and fossil-rich shorelines, while its traditional village preserves a glimpse of a quieter, pre-modern Persian Gulf way of life.

Hengam’s economy blends small-scale tourism, fishing, and the renowned production of delicate, lace-like handicrafts crafted by local women, offering a potential model for balancing ecological preservation with community-based economic benefit.

The islands of Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs occupy a more contentious position within the region’s geopolitical landscape. Historically, they functioned as waystations for trade and fishing communities, a pattern typical of the Persian Gulf.

Abu Musa holds economic importance due to its oil fields and deposits of red oxide, while the Tunbs are valued primarily for their strategic location. Together, these islands underscore the enduring geopolitical relevance of even the smallest landmasses in the Gulf.

Collectively, these lesser islands reveal the foundational rhythms of life in the Persian Gulf. Their economies remain deeply bound to the sea, with artisanal fishing continuing to provide sustenance and livelihood.

The cultural heritage preserved here is equally invaluable: distinctive dialects such as Komzari, traditional musical forms, and the masterful boat-building skills used to construct shows and lenjes, the iconic wooden sailing vessels of the region. Ecologically, these islands serve as critical sanctuaries for biodiversity, from Larak’s bird populations and Hengam’s dolphins to the nesting beaches of hawksbill turtles found across the archipelago.

In an era of rapid modernization, these islands function as guardians of both ecological balance and cultural memory. They remind us that Hormozgan’s archipelagic story is not solely defined by mega-projects or strategic chokepoints, but also by resilient coastal communities living in harmony with a demanding yet generous marine environment, preserving ways of life that have shaped the Persian Gulf for millennia.

Together, from the largest to the smallest, these islands form an indispensable, multifaceted, and breathtakingly beautiful component of Iran’s national heritage.

Behind the riots: Spy games, media spin, discarded monarchists and lessons from history

IRGC deputy chief warns of harsh response to any aggression against Iran

Araghchi appreciates Pakistan’s vote against anti-Iran UNHRC resolution

Discover Iran: Historical, natural, and economic tapestry of idyllic Hormozgan islands

ICE detains 2-year-old girl, sends her to Texas despite court order

VIDEO | Trump claims his 'Board of Peace' might replace the UN

VIDEO | Shadows of Rebellion: How Iran’s protests turned violent

FBI agent investigating Minneapolis deadly shooting resigns

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website