Discover Iran: Isfahan's landmark bridges, masterpieces of engineering and art

By Ivan Kesic

- The historical bridges of Isfahan are functionally unique, serving not only as crossings but also for water management, irrigation, leisure, ceremonies, and scenic viewing.

- They were built within a century of Safavid rule, reflecting their vision of a cosmopolitan capital, designed to awe visitors and compete with the grandeur of the world's greatest cities at the time.

- The use of multiple arches to distribute weight and manage floods showcases advanced hydraulic knowledge, influencing later Islamic architecture.

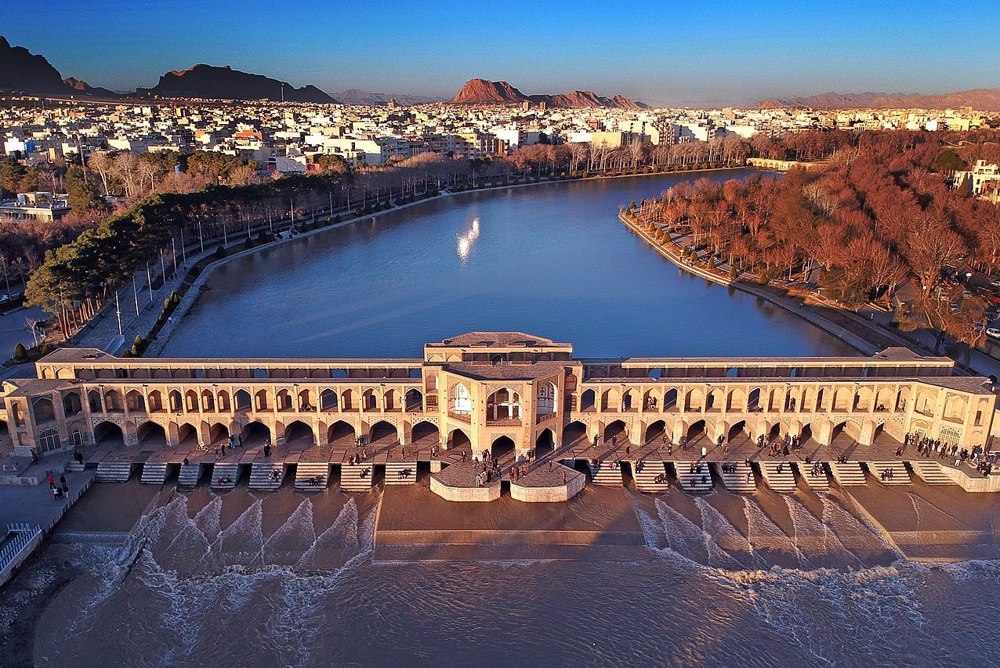

The iconic bridges spanning the Zayandeh River in Iran’s Isfahan province, including Si-o-se-pol, Khaju, Shahrestan, Jubi, and Marnan, stand as masterpieces of Safavid-era engineering.

These architectural marvels seamlessly blend structural ingenuity with artistic splendor, functioning both as essential river crossings and enduring symbols of Iranian cultural heritage.

During the Safavid era, under Shah Abbas I (1587-1629), Isfahan, celebrated as “Half of the World,” emerged as a thriving capital city renowned for its urban planning and architectural brilliance.

The bridges of the Zayandeh River were more than functional infrastructure; they served as social hubs, marketplaces, and stages for artistic expression.

Safavid bridges mark a significant advancement over earlier Timurid, Ilkhanid, and Seljuk designs, featuring intricate tilework, multi-arched structures, and thoughtful integration with the river’s flow, a testament to sophisticated hydraulic and engineering mastery.

Shahrestan Bridge

The oldest known original bridge in Isfahan is the Shahrestan Bridge, also known as the Jay Bridge or Jasr Hossein Bridge, today in the eastern part of the city, on the old riverbed.

According to historians and archaeologists, the foundation of the Shahrestan Bridge dates back to the Sassanid period (3rd-7th century AD).

During the Buyid and Seljuk periods (10th-12th century AD), this bridge was the only important bridge on the Zayandeh River within the city, and it seems that it was probably repaired and parts were added to it during these periods.

Built of brick and adobe with stone foundations, it served as a military and trade route. With a length of 112.5 meters on 11 spans and a width of 4.8 meters, it is a simpler structure compared to later bridges.

It took its final form during the Safavid period, when a toll gate was built on the northern side. Today, it is used only for pedestrian traffic.

Marnan Bridge

The Marnan Bridge is located to the west of the city, about eight kilometers upstream from the Shahrestan Bridge. It appears in historical records under alternative names including Marbanan, Marbin, Sarfaraz, and Abbasabad.

The prevailing scholarly view suggests initial construction under Shah Tahmasp I (1524-1576), with later renovations by Jolfa Armenians during Shah Suleiman's reign (1666-1694).

The 180-meter structure spans north-south with seventeen arches, varying in width from 4.7 to 6.6 meters. A Qajar-period city gate once stood adjacent to the bridge.

It is similar in simple design and structure to the Shahrestan Bridge, as both are built with stone foundations and piers, pointed brick arches, and relief openings above the piers.

In the 1970s, the bridge underwent restoration, as flooding destroyed six southern spans that were subsequently repaired.

Si-o-se-pol, part of the city spine

True Safavid bridge engineering begins with Si-o-se-pol (Bridge of 33 Arches), known in history by various names, including Allahverdi Khan Bridge, Abbas Bridge, Chaharbagh Bridge, Jolfa Bridge, Zayandeh River Bridge and the Great Bridge.

With the relocation of the Iranian capital from Qazvin to Isfahan in the late 1590s, Shah Abbas I ordered an extensive expansion of the city further south, towards the Zayandeh River.

The backbone of the urban plan was the 1.65 km long Chaharbagh boulevard-garden, stretching in a north-south direction, on the southern side of which was Si-o-se-pol.

The importance of connecting the two banks was in the royal gardens south of the river, as well as the newly built New Jolfa district for Armenian refugees from the Ottoman attacks.

The axis of Chaharbagh extended from the center of the new Islamic city in the north, across Si-o-se-pol, to the 2.4 km distant Hezar Jarib gardens in the south.

The bridge has an atypical location compared to other Iranian and world bridges, given that it was not built on the narrowest, but rather the widest part of the river, with a length of about 300 meters.

Si-o-se-pol as a royal ambition

Si-o-se-pol was built under the supervision of Allahverdi Khan, a famous Safavid general who distinguished himself in victories against the Portuguese colonial empire, for which he gained great fame and wealth.

Allahverdi Khan sponsored numerous other buildings, including the Khan Madrasa in Shiraz, which educated Mulla Sadra, a noted philosopher whose thought had an immeasurable influence on the development of modern Iranian theology, science, and politics.

Armenians sometimes wrongly attribute the construction of the bridge to Allahverdi Khan (d. 1662), a general of Armenian origin and namesake of the actual superintendent whose career also progressed from gholam to commander.

Modern European travelogues often state that the grandiose bridges and buildings were the result of competition between Iranian nobles, but modern scholars consider such a hypothesis unlikely.

The prevailing opinion today is that the monumental projects have primarily a political connotation and are the fruit of Abbas I's imperial ambitions.

They were built with the aim of impressing both neighboring and European allies or rivals, since they place Isfahan in a superior position compared to Ottoman Istanbul and Mughal Delhi.

At this time, Isfahan had a population of between 600,000 and 1,100,000, making it the largest or one of the largest cities in the world, along with the two mentioned above, as well as Beijing, Paris, and London.

In addition to its bridge function, Si-o-se-pol also served as a low dam that held back water to supply numerous residential units and city gardens using canals (maadi).

Since summer is a drought and the river often dries up completely, Abbas I and earlier Tahmasp I tried to compensate by building a canal that would redirect part of the Karun River's flow to the Zayandeh River (the predecessor of the Kuhrang Canal opened in the 1950s).

However, the project was abandoned after several years of work due to the difficulty of breaking through the solid rocks of the Zagros Mountains, cold temperatures, and high costs.

Si-o-se-pol as a symbol of coexistence

Si-o-se-pol is a monument to the ethno-religious diversity of Isfahan because it connected the Muslim north with the Christian New Jolfa in the south, and the superintendent Allahverdi Khan was an ethnic Georgian and a born Christian who converted to Islam as a young man.

This syncretism is also emphasized in the design of the bridge itself, with 33 main spans, which Christian Armenians see as symbolic of the number of years of Jesus Christ.

On the upper level, above each main span, there are two smaller arches, with an additional arch above the pier, making a total of 99 arches and symbolizing the number of Allah's names in Islam.

There is also unfounded speculation that the bridge originally had 40 spans, which is evidently incorrect, considering that the earliest travel writers, such as García de Silva y Figueroa, Pietro Della Valle and Thomas Herbert, gave either the same length or number of spans as today.

In travelogues by some authors, such as Herbert and William Ouseley, it is mentioned that the bridge has 34 arches, but this undoubtedly includes an additional shorter arch under the southern ramp.

Technical mastery of Si-o-se-pol

The structural length of the bridge deck is 295 meters, or 368 m with access ramps. The stone piers are 3.5 m wide, with clear spans between them of 5.57 m.

Engineers anchored the structure to stone foundations, later reinforced with concrete during 20th-century preservation. The original builders also employed masonry bound with traditional saruj mortar for water resistance.

The essential design of the bridge's facade is an elegant double arcade with four-centered brick arches, in use in Iranian architecture since the 10th century. As in the case of Chaharbagh, there is a harmony of function and aesthetics.

The width of the bridge is 13.75 meters, of which 9 meters is the paved road on the deck, bordered by two high parapet walls. On both outer sides of the latter are galleries and smaller arcades with 99 arches.

These side spaces create two additional walkways accessed by eight cross entrances on both parapet walls; however, the narrowness of 0.76 m and the height of the transverse openings lower than the average person indicate that they are not intended for pedestrian traffic.

Instead, the limited dimensions testify that the architect wanted to create the ambiance of an intimate space intended for sedentary relaxation and enjoyment with a spectacular view of the river, gardens, buildings, and other bridges.

Remarkably, the double-tiered arcade creates natural ventilation—lower arches channel river breezes while upper decorative openings enhance airflow.

In addition to the main and two side galleries, the bridge also has two upper walkways on the parapet walls (above the galleries) and a lower one, which is accessed by a staircase located inside the pier towers at the corners of the bridge.

The lower promenade in the substructure is vaulted with flattened pointed arches and its level is raised several decimeters above the bottom of the paved riverbed.

The platforms between the piers also create private spaces for leisure and relaxation, and the transition between them is made via toothed stone cubes at the same level, which also serve as a spillway.

The bridge's hydraulic ingenuity emerges in its sloped pavement and embedded sluice gates, allowing it to function simultaneously as a weir.

Safavid builders also incorporated acoustic principles into the vaulted galleries, where whispers carry clearly across the central roadway. Most of the piers are structurally solid, two serve as staircases, and an additional ten function as chambers, sometimes with windows on the bridge facade.

Along the piers on the upstream side are half-conical buttresses serving as breakwaters, as well as four semi-cylindrical ones that rise to the full height of the bridge and have symmetrical equivalents on the opposite side.

The stone foundation slab on the riverbed is twice as wide as the bridge, about 30 meters, and extends half of it downstream to prevent the formation of hydrodynamic scour holes.

Upon completion in 1602, it became one of the largest functional masonry bridges in Iran, comparable in size only to the older Band-e Kaisar in Shushtar, Old Bridge in Dezful, Sarcheshmeh Bridge near Maragheh, Broken Bridge in Khorramabad, and Dokhtar Bridge and Kashkan Bridge in Lorestan.

The crown adorning the eastern facade and the toll gate situated in the bridge's northern landscape were additions from the Qajar period, later demolished during the Pahlavi period. Since the late 20th century, it has been used only for pedestrian traffic.

Impressions of Si-o-se-pol

For centuries, it has left a strong impression on visitors and European travel writers, beginning with the brothers Anthony and Robert Shirley, who stayed in Isfahan during its construction.

García de Silva y Figueroa visited the city in May 1618 and described the bridge as magnificent and "one of the most celebrated structures in the whole empire," comparing it in grandeur to the Qeysariyeh Bazaar in the city of Lar.

A year later, in early July 1619, Pietro Della Valle portrayed Si-o-se-pol as a stunning bridge, similar in both purpose and scale to the Chaharbagh. He also recounted the Tirgan, an age-old Iranian water festival celebrated enthusiastically by the people of Isfahan.

The festivities involved laughter, leaping, shouting, and even tossing clothed individuals into the river, a tradition in which Shah Abbas I himself took part.

Once Abbas and his entourage grew weary of the waterplay, they would retire to the bridge alongside ambassadors and guests, relaxing with refreshments and conversation.

In January 1620, Della Valle also attended the feast of the Epiphany, on which Armenian Christians celebrate the baptism of Jesus according to their calendar and hold a rite of blessing the waters by placing a cross in the Zayandeh River.

Abbas, nobles and numerous citizens participated in these ceremonies, and during their holding, the Si-o-se-pol was closed to traffic to avoid disrupting the clergy and the procession.

Thomas Herbert visited the city in April 1628 and recorded the solemn welcoming ceremony upon the entry of a delegation from the south, through Chaharbagh and over Si-o-se-pol.

The English delegation was warmly welcomed by various Iranian and Armenian dignitaries and the city's masses, accompanied by the playing of drums, flutes and tambourines.

Herbert was amazed by the bridge and gardens of Chaharbagh and Hezar Jarib on the same axis, calling them a paradise, with the comment that they were not comparable to anything seen in Asia.

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier described it as "truly a very neat piece of architecture, possibly the neatest in the whole country" and compared it to the Pont Neuf in Paris, the oldest standing bridge across the river Seine in Paris, completed five years later.

During the 17th century, the bridge was also praised by Adam Olearius, André Daulier Deslandes, Jean Thévenot, Jean Chardin, Jan Janszoon Struys, John Fryer, François Sanson, and Engelbert Kaempfer.

Among later travelogues, the notes of William Ouseley from August 1811 are interesting. He states that the river was partially dried up, while at the same time, the deeper water in the bridge reservoirs served the local Armenians as a spawning ground for carp.

Ouseley claims that Shah Abbas II, during his reign in the mid-17th century, had the entrances to the pier chambers bricked up because he was dissatisfied with the inappropriate paintings inside.

Like older authors, around 1840, Pascal Coste describes the leisure function of the bridge, stating that in the evenings, citizens come to cool off, drink tea and enjoy the beautiful view of the landscape and skyline with domes and minarets.

Si-o-se-pol also left a strong impression on George Nathaniel Curzon, a British politician and later Viceroy of India, who in 1889 described it as "the most stateliest bridge in the world."

Several years later, Percy Sykes described it as "even in decay must rank among the great bridges of the world."

The bridge's multi-storey structure and dual role as a crossing and gathering place with a viewpoint also inspired contemporary Iranian bridges, such as the Nature Bridge (or Tabiat Bridge) in Tehran.

Khaju Bridge

The Khaju Bridge is located about two kilometers downstream from Si-o-se-pol. It is aesthetically and functionally similar, but is more than half as short.

It is laid out on the urban axis that connects Naqsh-e Jahan Square in the north with the Takht-e Fulad cemetery in the south, and it may have replaced a 15th-century bridge that connected Isfahan to the old road to Shiraz.

The bridge was built in 1650 under the rule of Shah Abbas II, at a time when the monarch had shifted eastward the urban development of Isfahan. It is named after the Khaju neighborhood or Chaharbagh garden to its north.

Khaju Bridge is also variously known as the Hasanabad Bridge for the old neighborhood to its north, as the Baba Rukn al-Din Bridge for a nearby mausoleum shrine to its south, and as the Shahi Bridge, because of its royal associations.

Stretching 132 meters long and 12 meters wide, the bridge served multiple urban functions, like Si-o-se-pol. Beyond its practical function as a crossing and a weir, the Khaju Bridge doubled as a lively gathering place for relaxation and amusement.

With two arcades on the facade, it is similar to its model, but with three important differences. The first is that at intervals between the lower arches, there are two smaller upper ones, instead of three as in its predecessor.

The second is that the intervals are not of equal dimensions; four of the eighteen lower ones (not counting the pavilions) are shortened, along with the double arches above.

Finally, the third difference is the pavilions at the ends and in the center, where Shah Abbas II once sat to enjoy the view. The cross-section is almost identical to Si-o-se-pol.

The central pavilion is octagonal in shape and has one arch on each side on both floors. The bridge's pavilion and central aisle were once decorated with 18th-century tiles, notable for their striped patterns and yellow hues.

Though most painted murals have faded, travelers like Jean Chardin recorded inscriptions, including one that read: "The world is but a bridge—pass over it, weighing all you encounter. Everywhere, evil surrounds good yet surpasses it."

By closing the weirs of Khaju Bridge and Si-o-se-pol, the Safavid rulers transformed the river into a lake near Saadatabad, a royal retreat. The bridge thus became a venue for royal festivities, including fireworks and boat races.

Historical accounts, such as those by Vali Qoli Shamlu, describe lavish Nowruz celebrations with the bridge adorned in lights and flowers, attended by Shah Abbas II and his court. Poets like Saeb Tabrizi commemorated these events in verse.

Jubi Bridge

The Jubi Bridge, literally the Rivulet Bridge, is another bridge from the reign of Shah Abbas II, completed in 1665 between Si-o-se-pol and the Khaju Bridge.

The bridge is also known as Saadatabad Bridge, after the nearby garden, Haft Dast Bridge, after the palace in that garden, and Lake Bridge, after the Khaju Bridge reservoir.

Unlike the aforementioned public bridges in Isfahan, the Jubi Bridge was for the exclusive royal use as it connected riverfront palaces and gardens across the two banks of the Zayandeh River.

Built as a modest, single-level bridge with 21 arches, it served as both a functional crossing and an aqueduct, channeling water to the royal Saadatabad Garden to the south and the Karan Garden to the north.

Typical of the Safavid bridges of Isfahan, it was built with stone foundations and piers, as well as brick arches. Some link its name to wood, suggesting it replaced an earlier timber bridge called Chubi (Wooden).

The bridge is 147 meters long and 4 meters wide. At regular intervals of seven arches, there are two octagonal pavilions for leisure activities, with five windows on both sides.

US missiles launched from residential areas of neighboring countries: Tehran

Pezeshkian: Nakhchivan aerial bombardment not linked to Iran

US, Israeli targets struck in mass IRGC missile, drone strikes

Supporting anti-Iran aggression constitutes complicity in war: Pezeshkian tells Macron

Iran Parliament hails election of new Leader, pledges allegiance

Iran's defense and security institutions unite in steadfast allegiance to new Leader

Profile: Ayatollah Seyyed Mojtaba Khamenei, third Leader of the Islamic Revolution

Resistance groups congratulate Iran on Ayatollah Mojtaba Khamenei’s election as new Leader

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website