Austrian press casts Iranian ties as threats, spotlighting bias and selective freedom

By Sheida Eslami

The new wave of reports in Austria’s mainstream media, especially in Der Standard and Falter, has once again brought Iran and media outlets associated with it into the public sphere as a “crisis-creating” issue.

This time, the pretext is not directly the activity of a television network, but rather the professional presence of individuals, training courses under the title of “peace,” and media connections within the framework of a professional body – the Austrian Press Club.

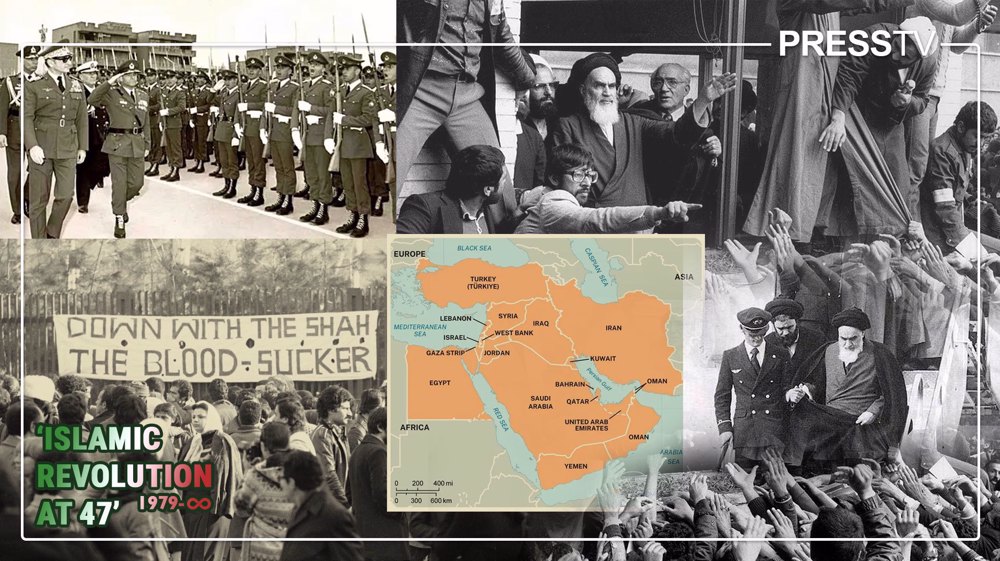

Nevertheless, the tone, conceptual framing, and value-laden language of these reports indicate that we are not facing a case-by-case discussion or a simple professional concern. We are rather witnessing the reproduction of the same familiar pattern that was previously employed in dealing with Press TV, Iran’s leading international media network.

The report by Der Standard on February 9, 2026, focusing on “Iranian connections” and questioning the legitimacy of a training course, effectively began from the very point at which it had already predetermined its desired conclusion: Any professional link with Iran is potentially regarded as a threat to media independence.

Falter continued this line more explicitly and, by using terms such as “propaganda,” attempted to redefine these connections not within the framework of media exchange, but as political influence. In one of its reports, the weekly addressed a new wave of criticism against the Austrian Press Club, this time tied to the unfounded allegation of “promoting the narratives of the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

The report, published on February 10, stated that the cooperation of some club members with institutions and media affiliated with Iran – including participation in training or media programs – has caused concern among a part of Austria’s media community.

Media observers claim that these collaborations are not conducted within the framework of professional exchange, but rather in the direction of normalizing or reproducing so-called “the Iranian government’s propaganda.”

✍️ Viewpoint - Austrian media and the West’s deepening structural hostility toward Iran’s Press TV

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) October 22, 2025

By Sheida Eslamihttps://t.co/RbC4ZinNhZ pic.twitter.com/O85vHQnbDb

By referring to the role of Iranian media in the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Falter attempted to redefine these connections within a political-security context and wrote that the Austrian Press Club, by ignoring existing sensitivities, has endangered its professional credibility.

At the same time, the report implicitly acknowledged that there is no clear legal prohibition against such forms of cooperation. However, the media pressure and the political atmosphere that have been created have effectively placed the club in a defensive position and turned it into the focal point of a public controversy.

In both texts, however, what is strikingly absent is a precise case-by-case examination, a distinction between professional activity and what is labeled “state propaganda,” and, most importantly, the application of the same standards these media outlets use when dealing with other international actors.

This is precisely the point at which the link between this new wave and an article previously published on the Press TV website becomes meaningful.

In that article, the main argument was based on the premise that the treatment of Press TV in Austria and Europe was not the result of a specific legal violation, but rather the product of a kind of “structural hostility”; a hostility in which media outlets outside the Western sphere are placed in the position of the accused from the outset, and then all their activities are reinterpreted under concepts such as threat, influence, or intelligence operations.

That article showed how the pressures were media-driven and discursive before they were legal, and how public opinion was prepared in advance to accept restrictions.

What we see today in the case of the Austrian Press Club is the continuation of the same logic, with the difference that this time the circle of targets has expanded. The issue is no longer just a television network, but any individual, institution, or initiative willing to cross the defined boundaries of the dominant narrative.

The concept of “peace journalism” is meaningfully brought into the arena in this context – a concept that by nature should be based on dialogue, pluralism, and the critique of dominant narratives, yet within this media framework, it is deemed acceptable only when it is politically “harmless” for institutions aligned with the Western media and propaganda apparatus.

✍️ Viewpoint - Iranian media’s global, narrative-shaping reach – acknowledged by Israeli ‘think tanks’ https://t.co/nyawrTP9Ee

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) December 11, 2025

By @Sheydaeslami pic.twitter.com/KxqKpJnlKU

A closer analysis shows that these confrontations are rooted less in professional concerns than in a deeper anxiety within the Western media structure: anxiety over the collapse of interpretive monopoly.

Media outlets such as Press TV, regardless of agreement or disagreement with their content, embody the reality that the narrative of the world is no longer produced by a single center.

The sharp, labeling, and at times hysterical reaction to any sign of this pluralism is an attempt to restore the old order – an order in which “media freedom” is not a universal concept, but a privilege whose legitimacy must be affirmed by those who endorse Western standards.

The fundamental contradiction lies precisely here: Media outlets that consider themselves guardians of transparency and freedom of expression, in practice promote an environment in which professional cooperation with certain media is considered suspect from the outset, not on the basis of actions, but on the basis of identity; not on the basis of assessing bias toward imperialism, but on the basis of the labels attached to any voice that differs from and falls outside the track of Western mainstream media.

This is the same dangerous logic that, if consolidated, empties journalism’s professional independence from within and makes it subordinate to geopolitical considerations, factional interests, and unilateral, power-centered expediency.

Ultimately, the new pressures regarding the Austrian Press Club affair should be understood not as a deviation, but as part of a process – a process that previously targeted Press TV and today targets any form of cooperation, training, or media presence connected to Iran.

More than anything, this process signals a crisis of media self-confidence in the West; a crisis that, instead of confronting rival narratives through debate, critique, and comparison, has chosen the simpler path of labeling and gradual exclusion – and under current conditions, when Iran is at the center of attention of free-minded people, independent journalists, and awakened consciences around the world, is intensifying it.

Experience has shown that such a path leads not to the strengthening of media freedom, but to the weakening of the very principles these media claim to defend, and ultimately removes the mask from their faces.

Sheida Islami is a Tehran-based writer, poet, media advisor and cultural critic.

(The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Press TV)

Iran’s uneven fight against US-led financial firewall

Iran joins club of countries with 110 advanced cell therapy products

Zelensky seeks 20-year US guarantee to ink Ukraine-Russia peace deal

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Iran says ball in US court to prove seriousness about making deal

Austrian press casts Iranian ties as threats, spotlighting bias and selective freedom

Munich 'circus' excludes Iran’s elected representatives, platforms ‘regime change’ lobbyists

Israeli reservists exploited secret bombing intelligence to bet on Gaza strikes

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website