Echoes of Alvand: How Iran shaped Iqbal Lahori’s poetic soul and philosophical vision

By Humaira Ahad

“My grave is the shrine of resolve and courage;

for I taught the dust of the path the secret of Alvand.”

Allama Muhammad Iqbal’s invocation of Alvand, the mountain overlooking Hamadan in western Iran, is not a casual geographic reference. For him, Hamadan was part of a deeper civilizational memory.

His family, though settled in Sialkot, present-day Pakistan, at the time of his birth in 1877, traced its lineage to Kashmir, a region whose Islamic culture was profoundly shaped by the arrival of Mir Syed Ali Hamadani, the great Islamic scholar from Hamadan.

That movement of ideas from Iran to Kashmir formed the spiritual background of Iqbal Lahori’s early world and literary pursuits.

His poetic gesture towards Alvand was homage to Iran’s stunning landscapes, intertwined with the intellectual and spiritual history from which his ancestral heritage drew its inspiration.

Philosopher inspired by Iran’s intellectual tradition

In the summer of 1907, Iqbal left Cambridge for Heidelberg to study in Germany.

Later that year, he submitted his doctoral thesis, “The Development of Metaphysics in Persia,” at the University of Munich. That work would quietly shift the way Persian philosophy was studied in Europe.

Iqbal began with Zoroaster and moved through centuries of Iranian thought, mapping out theological and philosophical debates that had remained largely unknown in Western scholarship.

He introduced European readers to Suhrawardi, Mulla Sadra, and Hadi Sabzavari, names that had scarcely appeared in Western academic writing at the time.

Iqbal was positioning Persian philosophy as a central strand of the Islamic intellectual tradition.

Later, in his masterpiece Javid Nama, the Pakistani poet returned to Zoroaster, casting him as a symbol of prophetic perseverance in a world threatened by Ahriman. The intellectual terrain he charted in Munich reappeared throughout his poetic universe.

🎥 Iqbal: The Eastern Wisdom - Part 1

— Press TV Documentary (@presstvdoc) November 6, 2025

🔻Allama Muhammad Iqbal's birthplace, his family members' personalities, and how all this affected the way his personality and way of thinking formed are depicted.

🗓 Saturday, November 8th

🕧 00:30 | 05:30 | 11:30 | 16:30 | 21:30 GMT pic.twitter.com/OlSXsNnDF5

Why did Iqbal turn to Persian?

By the 1920s, Iqbal had made a conscious literary choice: his central philosophical poetry would be written in Persian, not Urdu.

The audience for that decision was not limited to Iran. Persian was still a connecting string across South Asia, Afghanistan, and Central Asia, a language that carried centuries of metaphysics, mysticism, and political thought.

Iqbal saw Persian as a civilizational archive, one that preserved the East’s long conversation on love, selfhood, justice, and the human relationship with the Divine.

The Persian ghazal tradition and the masnavi form are both centred on ishq (creative love) as a force of transformation. That focus allowed Iqbal to frame love more than a sentiment. He regarded it as the inner power that gives rise to moral agency.

In doing so, Iqbal used Persian to argue for an intellectual identity that resisted the flattening influence of Western materialism.

For Iqbal, Persian was also the most precise medium available to articulate ideas of khudi (individuality) and humanity’s moral vocation.

In 1923, he published Payam-e Mashreq, his answer to the German philosopher Goethe’s West-östlicher Divan.

In 1927, Zabur-e Ajam (“Persian Psalms”) was published, whose final section, Gulshan-e Raz-e Jadid, re-examined the metaphysical questions first posed by the 14th-century Iranian Sufi poet Mahmud Shabistari.

And in 1932, he completed Javid Nama, the work he called the “book of eternity,” where Rumi appears as his guide through the spheres of existence.

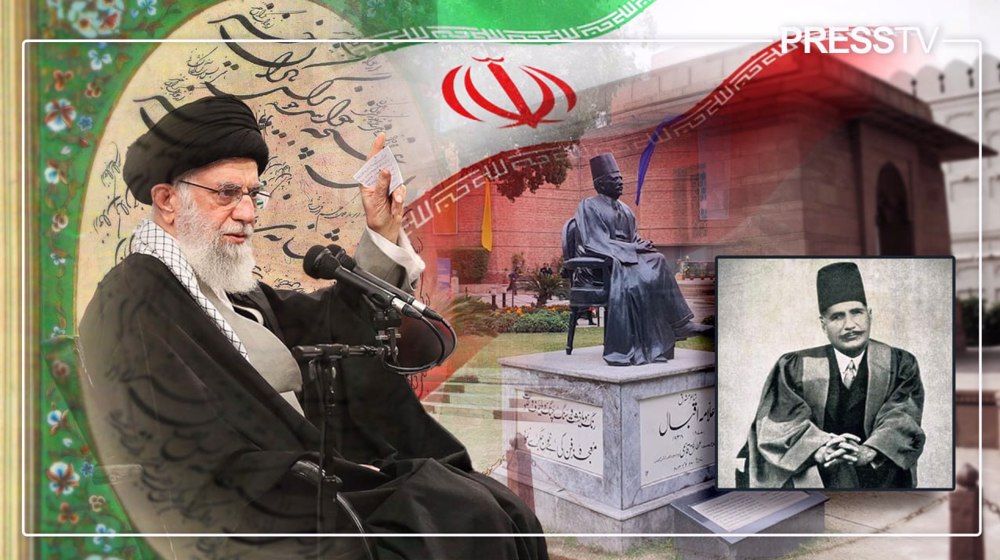

Leader of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei, who has often praised Iqbal’s works, once described the Pakistani poet’s Persian works as exceptional achievements.

“There are a large number of non-Persian speaking poets in the history of our literature, but none of them reaches the excellence of Iqbal’s Persian poetry,” he said.

For Ayatollah Khamenei, Iqbal’s mastery of Persian showed an instinctive understanding of the philosophical and spiritual registers embedded in the language.

🎥 Iqbal: The Eastern Wisdom - Part 2

— Press TV Documentary (@presstvdoc) November 8, 2025

🔻Allama Muhammad Iqbal's birthplace, his family members' personalities and how all this affected the way his personality and way of thinking formed are depicted.

🗓 Sunday, November 9th

🕧 00:30 | 05:30 | 11:30 | 16:30 | 21:30 GMT pic.twitter.com/3gWjPV625F

Rumi: the guide who stands at the centre

For Iqbal, the Persian mystic Molana Rumi stood at the centre of the Eastern world. Rumi was the teacher, the guide, the mirror in which he saw himself.

Rumi’s presence runs through all of Iqbal’s Persian writing. Iqbal had admired him since his student days, calling him in Hegel’s phrase “the excellent Rumi.”

In Javid Nama, Iqbal imagines his journey through the cosmos with Rumi as his companion and guide.

Iqbal chose the meter of the Masnavi so he could move in and out of Rumi’s cadences, quoting him without disrupting the flow.

Rumi’s language gave him a vocabulary for a God who was not distant but dynamic, and for a human self that was meant to grow and not dissolve.

Rumi represented the model of a thinker who fused intellect with the energy of love, a combination Iqbal believed was essential for modern Muslim societies.

Through Rumi, Iqbal found a language of movement, where love (ishq) was not surrender but creative energy, and where the awareness of individuality (khudi) was a reflection of divine possibility.

Rumi’s idea of Kibriya, divine grandeur, shaped Iqbal’s understanding of God as a source of perpetual creativity and the recipient (man) of the “divine illumination is not merely a passive recipient” but an individual who requires discovering the divine power within himself.

1- ✍️ Feature - ‘Poetic genius’: Allama Iqbal Lahori in the words of Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) November 9, 2024

By Humaira Ahadhttps://t.co/S3fa8X69v4 pic.twitter.com/lv0glc3BQr

Iran, the East and the question of identity

Iqbal’s optimism about Iran’s potential appears explicitly in one of his well-known verses:

“If Tehran could become the Geneva of the Orient,

The fortunes of this world might change.”

Experts say that the poet’s vision found resonance in post-revolutionary Iran.

Leader of the Islamic Revolution has also drawn connections between Iqbal’s ideas and Iran’s own self-definition after the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Iran’s founding slogan of “Neither East nor West” echoes in spirit through Iqbal’s insistence that Muslim societies must cultivate an independent centre of gravity rooted in their own philosophical and spiritual heritage.

“Had he been alive today, he would have seen a nation standing on its feet, infused with the rich Islamic spirit and drawing upon the inexhaustible reservoirs of Islamic heritage, a nation that has become self-sufficient and has discarded all the glittering western ornaments and is marching ahead courageously, determining its targets and moving to attain them, advancing with the frenzy of a lover, and has not imprisoned itself within the walls of nationalism and racialism,” Ayatollah Khamenei said.

Many Iranian thinkers have seen Iqbal as a precursor to their own political and spiritual reawakening.

Researchers in Iqbal thought say that the poet saw in Iran a potential centre of civilizational balance, a place where spiritual independence could resist the pull of both colonial modernity and empty nationalism.

Iqbal’s engagement with Iran shaped his philosophy, his poetry, and the language he chose to write his most important works.

Nearly ninety years after Iqbal’s death, his presence in Iran remains active, in universities, literary gatherings, and political reflections.

The mountains of Alvand that he once invoked still stand, and the questions he posed about selfhood, freedom, faith, and civilisation continue to travel between Tehran, Lahore, and the Kashmir Valley his ancestors once called home.

Leader’s advisor warns of ‘deep’ retaliatory strikes into occupied territories

US Department of Justice releases millions of Epstein files, then pulls pages citing ‘rape’ by Trump

VIDEO | EU blacklists anti-terror organization

VIDEO | 44th Fajr Theater Festival underway in Tehran

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

VIDEO | Oil workers' march in support of reform of Venezuela's main oil law

VIDEO | Malaysians hold rally in front of Iranian embassy to condemn US, Israel threats

Israel to partially reopen Rafah border crossing after long closure

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website