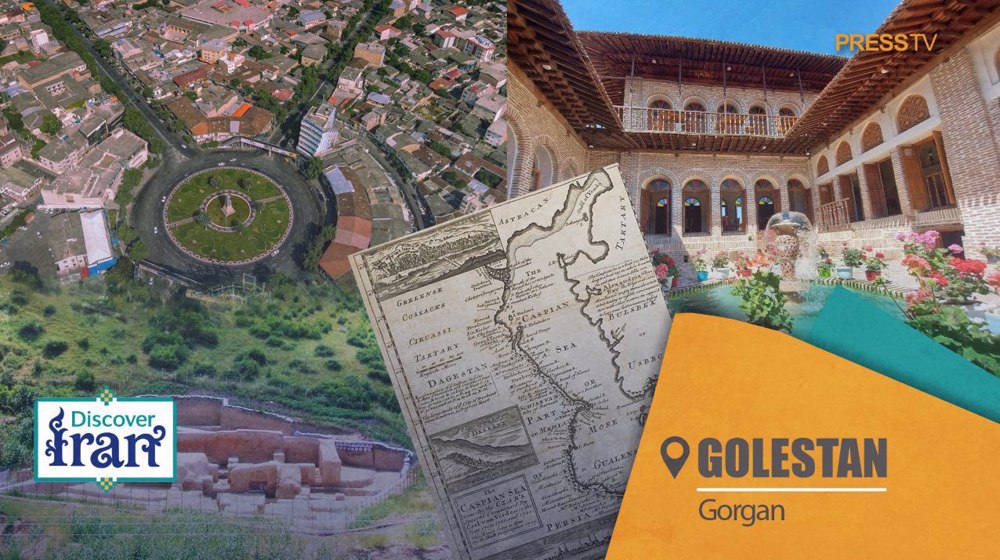

Discover Iran: Gonbad-e Qabus, a millennium-old tower of brick and geometry in Golestan

By Ivan Kesic

Of its many remarkable features, the Gonbad-e Qabus is most distinguished by its staggering height and pure geometric form, a revolutionary design that made it a prototype for mausoleum towers across the Islamic world.

Despite being a millennium old, the structure's incredible structural integrity showcases a sophisticated mastery of brick engineering and mathematics, allowing it to dominate the landscape after surviving earthquakes, climate, and even warfare.

While often cited as Iran's tallest brick tower, the Gonbad-e Qabus, at a clear height of 52 meters, finds its rivals in the minarets of Isfahan's Imam Mosque, which reach an identical height, and potentially in other Seljuk minarets that may have originally surpassed it before erosion.

Rising from the plains of northern Iran like a golden spear aimed at the heavens, the Gonbad-e Qabus is a masterpiece of early Islamic architecture whose silent, soaring form has dominated the landscape for over a thousand years.

For a millennium, the Gonbad-e Qabus has stood as an unyielding sentinel over the Golestan plain in northeastern Iran, a breathtaking mausoleum tower built for the Ziyarid ruler and literati, Qabus ibn Voshmgir.

Soaring to a height of 52 meters from its ten-meter artificial mound, this colossal structure of unglazed fired brick is the only surviving monument of an old city, the once-great center of arts and science obliterated by Mongol invaders.

Its stark, flanged cylinder, crowned by a razor-sharp conical roof, represents a revolutionary fusion of architectural ambition, scientific knowledge, and cultural exchange between the ancient civilization of Iran and the Central Asian steppes.

Beyond its immediate funerary purpose, the tower served as a powerful political symbol, an astronomical marker, and a prototype that would influence sacred building across Iran, Anatolia, and Central Asia.

Its flawless geometric proportions and incredible structural integrity, surviving earthquakes and wars, speak to a sophisticated understanding of mathematics and engineering in the Muslim world at the turn of the first millennium.

Patron and his power

The man who commissioned this monument was as complex as the structure itself. Qabus ibn Voshmgir, the fourth ruler of the Ziyarid dynasty, was a figure of stark contrasts.

His court became a refuge for some of the greatest minds of the Islamic Golden Age, including the world-renowned philosopher Avicenna and polymath Al-Biruni, who wrote his seminal work on calendars there.

Qabus himself was a poet and a proponent of rhymed prose, and his intellectual curiosity is immortalized in the tower’s very fabric.

The foundation inscription, composed in elegant rhymed prose, employs both the Muslim lunar and the Iranian solar calendars, precisely dating the tower's commission to between late September 1006 and mid-March 1007.

This dual dating system was a deliberate display of erudition and worldly power, reflecting a ruler who saw himself as a bridge between different cultural and temporal traditions.

Architectural revolution in brick and form

The architectural form of Gonbad-e Qabus is one of breathtaking simplicity and audacious scale. In plan, the building is a flanged circle, a perfect cylinder articulated with ten massive, right-angled buttresses that streak up its height like the edges of a sharpened pencil.

These flanges are not merely decorative; they serve a critical structural purpose, stiffening the slender brick shaft against wind and seismic forces, a technological innovation that allowed the builders to achieve such a staggering height.

The entire structure is constructed from fine-quality, pale yellow baked brick, which has been burnished to a deep gold by centuries of sun.

The technical mastery is evident in its near-perfect preservation despite the ravages of time, climate, and even reported shelling.

The building’s verticality is its defining characteristic, with a height-to-diameter ratio of approximately 1:3, a proportion that creates a sense of dynamic, skyward thrust unmatched by any other structure of its era.

Language of geometry and absence of ornament

What truly sets Gonbad-e Qabus apart from its contemporaries is its radical austerity. In an age where Islamic architecture was beginning to explore intricate surface decoration, this tower stands almost completely bare, its power derived solely from its pure, geometric form.

The only adornment is two inscription bands that ring the building, one above the doorway and another below the roof. The script, formed from cut bricks once covered with plaster, is tall and angular, a sober Kufic designed for legibility from a great distance.

This deliberate choice underscores that the building itself was the message. Its form speaks a universal language of geometry and proportion, a calculated representation of cosmic order and royal authority.

The conical roof, a direct translation into permanent materials of the royal tents used by Central Asian nomads, further illustrates the cultural synthesis at play, marrying the sedentary architectural traditions of Iran with the portable legacy of the steppes.

Prototype for the ages: the mausoleum tower legacy

The significance of Gonbad-e Qabus extends far beyond its own silhouette. It stands as a critical prototype, establishing a formal and symbolic vocabulary for mausoleum towers that would spread across the Islamic world.

Its conically-roofed, cylindrical form became a blueprint for commemorative structures throughout Iran, Anatolia, and Central Asia.

It marked the beginning of a regional cultural tradition of building monumental tombs not just for rulers, but also for literati and saints, elevating the mausoleum tower from a mere burial site to a lasting statement of cultural and intellectual achievement.

The tower’s influence is a tangible record of architectural exchange, demonstrating how a specific form could travel and evolve, connecting disparate regions through a shared architectural language.

Possible Iranian record holder

The question of the tallest pre-modern structure in Iran is a nuanced debate centered on the distinction between freestanding towers and architectural components.

The Gonbad-e Qabus, with a definitive height of 52.07 meters from its base (or 62 meters including its artificial mound), is frequently and rightly celebrated as the tallest freestanding brick tower in the country and a global benchmark of early Islamic engineering.

Its pure, unadulterated cylindrical form, rising from an open plain, makes its verticality profoundly imposing. However, this claim to absolute supremacy is rivaled by other magnificent structures from different stylistic periods.

The minarets of Isfahan's Imam Mosque, for instance, also reach a height of 52 meters, but they are not freestanding; they are anchored to the monumental portal (iwan) of the mosque, which alters their perceptual and structural context.

Furthermore, experts posit that some earlier Seljuk minarets, like the Ali minaret in Isfahan, may have originally exceeded 50 meters before centuries of erosion took their toll.

When considering entire buildings, the magnificent dome of the same Imam Mosque in Isfahan surpasses them all, reaching 54 meters.

Therefore, while the Gonbad-e Qabus holds an uncontested distinction in its specific category, the architectural landscape of Iran presents a family of giants, each claiming a different aspect of the height record, from freestanding towers to integrated minarets and vast, soaring domes.

Enduring significance and the test of time

The Gonbad-e Qabus is exceptional evidence of the power and quality of the Ziyarid state, which dominated a major part of the region during the 10th and 11th centuries.

Its continued stability is a testament to the exceptional development of mathematics and science in the Muslim world at the turn of the first millennium AD, an innovative structural design based on geometric formulae that achieved unprecedented height in load-bearing brickwork.

Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site for its outstanding universal value, the tower meets multiple criteria, being a masterpiece of human creative genius, demonstrating significant intercultural exchange, and being an outstanding example of a building type which illustrates a significant stage in human history.

It is not merely a relic but a living monument, continuing to function as a holy place visited by locals and a focal point for traditional events, its celestial form forever anchoring the past to the present.

Iran Army slams EU’s blacklisting of IRGC as ‘shameful’, ‘irresponsible’

Iran considers armies of EU states as ‘terrorist organizations’: Security chief

Sharif University scholars condemn US foreign policy as illegal, destabilizing

Pezeshkian says Iran seeks no war, vows 'decisive' response to any attack

Iran ready for both war and dialogue, ‘will not accept dictation’: FM Araghchi

Trump warns UK against enhancing China ties as PM Starmer hails reset

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Iran rejects threats, backs win-win diplomacy, Pezeshkian tells Erdogan

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website