Saddam's West-enabled chemical terrorism against Iran and indelible scars it left

By Ivan Kesic

As a recent conference in The Hague, Iran was unanimously elected to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) Executive Council, a move Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi described as a “meaningful step for all who believe in a world free of chemical weapons.”

“As a nation that has suffered deeply from Saddam’s chemical attacks during the 1980–1988 war on our people, Iran carries enduring wounds that still affect tens of thousands of victims and their families,” the top Iranian diplomat wrote in a post on X after the conference concluded.

Araghchi was accompanied to The Hague by Kamal Hoseinpur, a member of parliament from Sardasht, a city that the Iranian foreign minister said “stands as a global symbol of resistance, suffering, and the call for justice.”

“The people of Sardasht endured chemical attacks whose consequences continue even today, made worse by unjust US sanctions that restrict access to vital medicines and medical care,” he stated.

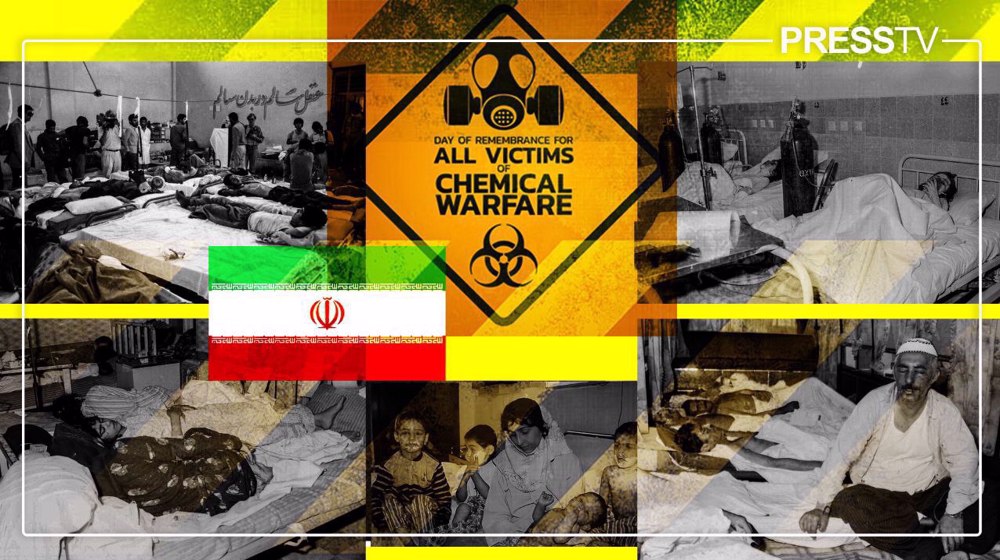

On Sunday, as the world marks the Day of Remembrance for Victims of Chemical Warfare, for the people of Iran, the events in Sardasht in the summer of 1987 are not a distant historical memory but a living legacy – one carved into the bodies and lives of the victims and survivors.

November 30 marks a solemn moment to honor those who have endured one of humanity’s most barbaric forms of violence and to reaffirm an international commitment to preventing its return.

For Iran, however, this commemoration carries a uniquely painful weight. The Islamic Republic remains the single largest victim of chemical weapons attacks since World War I – a grim reality rooted in the eight-year war imposed by the West-backed Ba'athist Iraqi regime.

The full truth of this monumental tragedy, according to activists, cannot be separated from the profound hypocrisy and deeply documented complicity of Western powers.

They provided the precursor chemicals, offered satellite intelligence to guide attacks on Iranian forces, shielded Baghdad from international censure, and in doing so became active partners in the gassing of Iranian soldiers and civilians.

A convention born from atrocity — and a victim left unheard

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), adopted in 1993 and entering into force in 1997, represented a landmark achievement in multilateral arms control. Its preamble expresses a resolve “for the sake of all mankind, to exclude the possibility of the use of chemical weapons,” reflecting lessons learned from the mass casualties of World War I.

To implement this commitment, the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) was created, entrusted with ensuring the global ban. The annual Day of Remembrance is an integral part of this mission, meant to honor victims and reinforce international resolve.

But for Iran, this architecture of global law and remembrance remains painfully incomplete.

While the world rightly condemns chemical weapons in modern conflicts, the unprecedented chemical bombardment Iran endured, one of the worst episodes in the post–World War I era, has never received the justice or acknowledgment warranted from those most responsible for enabling it.

The convention may have risen from the ashes of past atrocities, but for Tehran, the architects of its own national trauma not only escaped accountability—they continue to occupy positions of moral authority on the very world stage tasked with preventing such horrors.

Today is the Day of Remembrance for Victims of Chemical Warfare — honoring those harmed by these weapons.

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) November 30, 2025

In 1987, the Iraqi Ba'ath regime of Saddam Hussein pounded the western Iranian city of Sardasht with chemical agents, killing 109 people and injuring 8,000. pic.twitter.com/8XmrXlj5LT

Arsenal of the West: Building Saddam’s chemical capability

When Saddam launched his invasion of Iran in 1980, his military lacked much of the advanced weaponry needed for a prolonged and brutal war. That gap was soon filled, systematically and deliberately, by Western governments that saw in Baghdad a useful counterweight to the nascent Islamic Revolution in Iran. Their support was extensive, coordinated, and decisive.

Germany was among the most prominent suppliers, providing key chemical precursors and industrial technology essential for producing mustard gas and nerve agents.

The United States, in an act of staggering cynicism, supplied Saddam with some 500 tons of hazardous chemicals capable of being converted into mustard gas. This was not an isolated transfer but part of a sustained pattern of assistance.

France contributed modern weaponry, including Super Étendard aircraft used to strike Iranian positions, while Britain offered strategic planning expertise and intelligence support.

American corporations, often with full governmental awareness, facilitated the export of dual-use technologies, and even biological agents with “warfare significance,” obtained from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

Together, these actions transformed Ba'athist Iraq into a full-fledged chemical weapons power, arming a notoriously brutal regime with weapons that the world had already sought to ban.

Battlefield and beyond: Chemical warfare against soldiers and civilians

With his Western-fueled arsenal, Saddam deployed chemical weapons on a staggering scale. Estimates suggest that more than 100,000 chemical munitions were used against Iranian forces. This was not a sporadic or covert tactic; chemical warfare became a central pillar of Iraq’s battlefield strategy, especially after Iran began gaining ground in 1982.

Western complicity extended beyond supplying materials. The United States provided Saddam with satellite imagery identifying Iranian troop concentrations. As one former U.S. official chillingly admitted, “we were giving Saddam intelligence that laid out where Iranian troops were massing. Then he would gas the living daylights out of them.”

This was not merely battlefield brutality but an industrialized killing, enabled by foreign intelligence agencies.

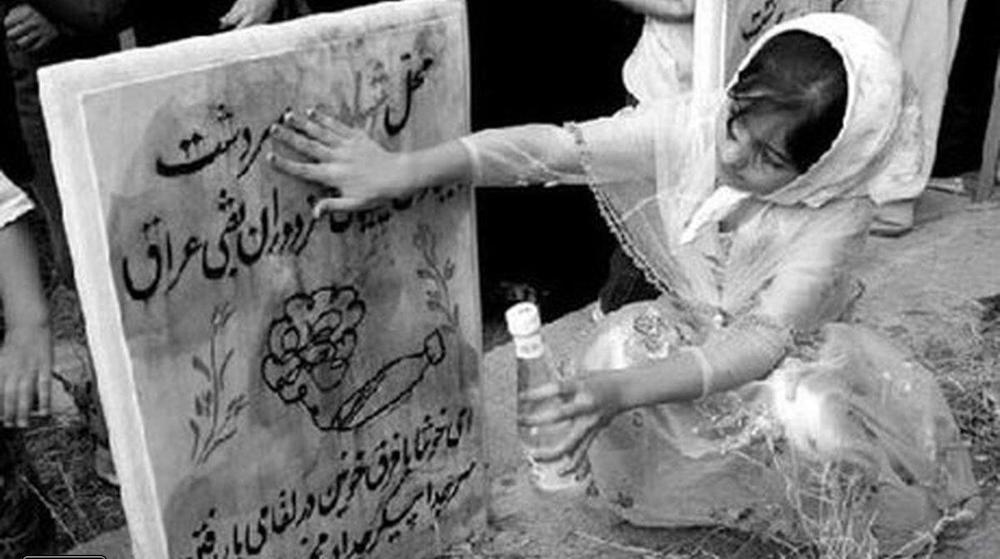

The terror did not stop at the front lines. In 1987, in one of the most notorious attacks on civilians, the city of Sardasht was bombarded with chemical agents, killing hundreds of people and injuring more than 8,000.

It was a stark message: no Iranian citizen -- soldier or civilian -- was beyond reach.

The humanitarian devastation of these attacks continues to shape lives across Iran today, with survivors still bearing the physical and psychological scars of a war waged with weapons the world had promised would “never again” be used.

As Araghchi stated at the Hague conference, the truth must prevail, and those who supported Saddam’s chemical weapons program must be held responsible.

“We urge Germany to release the results of its past investigations and commit to full and transparent investigations about the involvement of its companies and nationals in enabling Saddam’s atrocities,” he wrote on X.

“The judicial investigations by Dutch authorities, which led to the prosecution and conviction of one Dutch individual, are appreciated. However, we all know that it was the very minimum and showed only the tip of the iceberg.”

Iran’s foreign minister highlights the role of European countries in providing former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein with chemical weapons and called for independent judicial investigations.

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) November 26, 2025

Follow: https://t.co/mLGcUTSA3Q pic.twitter.com/BkMbq7ALgf

Halabja: a crime of revenge and Western obscuration for the allies of powerful nations.

The chemical warfare campaign reached its horrific peak in the Iraqi Kurdish city of Halabja in 1988. After Iranian and Kurdish forces briefly liberated the city during Operation Valfajr-4, Saddam sought a brutal revenge on a population he viewed as traitorous.

Iraqi aircraft dropped a lethal mix of chemical agents on the town, killing an estimated 5,000 men, women, and children in what remains one of the most infamous chemical attacks in modern history.

Historical records show that the massacre was intended as direct retaliation for the residents of Halabja welcoming Iranian forces. Yet the Western reaction to this mass killing was a study in hypocrisy and political expediency.

Despite possessing intelligence that monitored Iraqi military communications related to the attack, the Reagan administration worked to obscure Saddam's responsibility.

Washington launched a disinformation campaign, falsely suggesting that Iran shared blame for the gas attack, a claim that contradicted all available evidence.

This deliberate distortion exposed an uncomfortable truth: the so-called “red line” against chemical weapons was less a principled moral boundary and more a geopolitical instrument, one that could be bent or ignored when an ally was the perpetrator.

Diplomatic betrayal: Shielding the aggressor at the United Nations

Even as Iran endured relentless chemical assaults, it turned to the international institutions created to uphold peace and enforce global norms.

Tehran filed complaints and introduced draft resolutions at the United Nations, seeking condemnation of Iraq’s clear violation of the 1925 Geneva Protocol.

The response from major Western powers, led by the United States, was a profound betrayal. Rather than enforcing international law, the US actively pressured its allies to block any meaningful action against Saddam Hussein.

Through diplomatic maneuvering, they orchestrated a “no decision” stance on resolutions that would have formally censured Iraq. This protection ensured that Saddam paid no political price for his war crimes, effectively greenlighting the continued and escalating use of chemical weapons.

The episode revealed a stark double standard that continues to shape global politics: strict enforcement for some, impunity for others—depending on their alignment with powerful states.

By shielding Iraq, a permanent member of the UN Security Council rendered the institution powerless, turning the body tasked with maintaining global peace and security into a bystander. In doing so, it became complicit in one of the darkest chapters of modern warfare.

Iran’s Foreign Minister, Seyed Abbas Araghchi, delivered a speech at the 30th Annual Conference of the States Parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention in The Hague.

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) November 25, 2025

Follow: https://t.co/mLGcUTS2ei pic.twitter.com/HUhH7qTo1o

Living martyrs: Iran’s enduring legacy of suffering

The true cost of this complicity is measured not in tons of precursor chemicals or declassified cables, but in the broken bodies and shortened lives of tens of thousands of Iranians.

Four decades later, the campaign for justice for a large community of veterans suffering from the long-term effects of chemical exposure continues. These survivors – revered as “living martyrs” – bear daily witness to the enduring legacy of those attacks.

The consequences of mustard gas are lifelong and merciless. Survivors grapple with chronic respiratory illnesses, debilitating skin diseases, irreversible eye injuries, and heightened risks of cancers and genetic disorders that can be passed to future generations.

Every day, these veterans and civilians confront a mixture of physical pain and psychological trauma, living reminders of both the war itself and the nations that armed their aggressor.

Their medical needs – complex, costly, and never-ending – have become a substantial national burden for Iran. Yet the governments that enabled Saddam’s chemical arsenal have never been held accountable for the suffering they helped unleash.

The West supplied the weapons. Iran continues to shoulder, alone, the immense human and financial cost of caring for the victims – costs that will span generations.

Many US troops exploring ways to evade fighting in war on Iran: Anti-war activist

Indian journalist reveals severe Israeli censorship after escape from occupied territories

Iran blasts UN chief for downplaying US-Israeli atrocities

Iranian Navy fires missile towards USS Abraham Lincoln after promise of revenge

IRGC deploys new-generation missiles in latest wave of Operation True Promise 4

'We will crush you': Iran Armed Forces warn Iraqi Kurdistan against cooperation with US, Israel

Iran welcomes, awaits US escort of oil tankers through Strait of Hormuz: IRGC spox

As Hezbollah retaliates against Israel, Lebanese govt siding with aggressor: Expert

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website