The story of ancient Persia’s chromium steel

Nearly a thousand years ago, in what is now southern Iran, steelmakers were producing a metal that modern science believed did not exist until the industrial age.

Archaeologists investigating the village of Chahak have found evidence that craftsmen there were deliberately adding chromium to steel in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Chromium is the element later used to make stainless steel. In Europe, systematic experiments with chromium alloys began in the 1800s and led to stainless steel in the early 20th century. The Iranian material predates that work by roughly seven centuries.

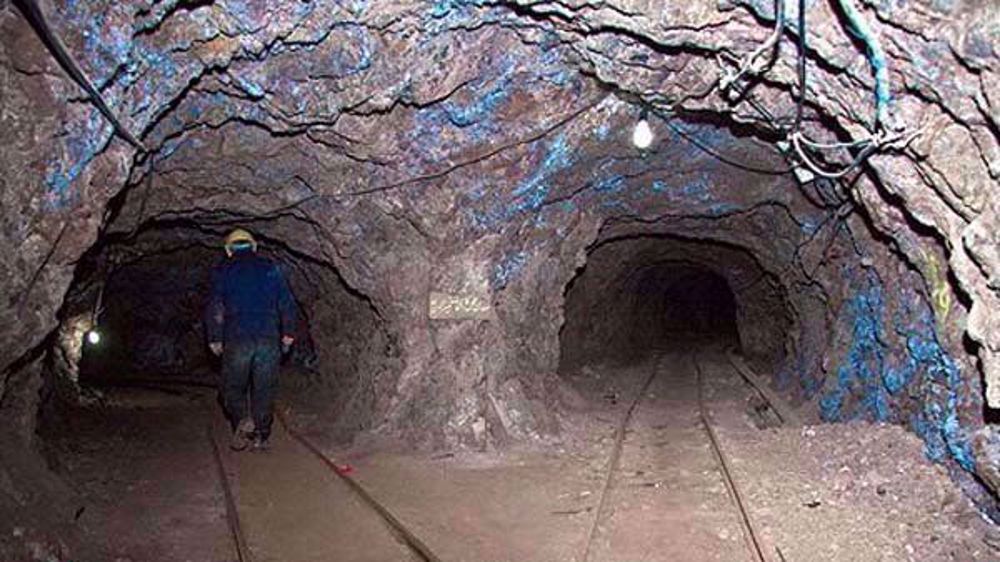

The discovery comes from the remains of a crucible steel workshop. Crucible steel was made by sealing pieces of iron inside thick clay containers and heating them in a charcoal furnace to temperatures high enough to melt the metal.

Inside the closed vessel, the iron absorbed carbon and liquefied, forming a dense, high-carbon steel when cooled. This method produced a more uniform material than earlier bloomery iron.

Fragments of broken crucibles are scattered along the southern edge of Chahak. A layer of debris, including slag — the glassy waste from metal production — was preserved beneath a dirt track.

Nearby are remains of ceramic pipes that fed air into furnaces, and accumulations of smithing slag indicating forging activity.

Radiocarbon dating of charcoal trapped inside a broken crucible and within smithing slag places production between the 10th and 12th centuries. Historical manuscripts from the medieval period describe Chahak as a center for producing pulad, the Persian term for crucible steel.

Laboratory analysis of slag and metallic droplets trapped within it revealed something unexpected. The iron prills repeatedly contained around one per cent chromium by weight.

The slag itself showed chromium oxide. The concentrations were consistent across multiple samples, suggesting that chromium was not a random impurity in the ore but part of the production process.

Researchers believe the chromium was introduced in the form of chromite, a naturally occurring chromium mineral. The region contains chromite deposits, and small additions of the mineral to a crucible charge would account for the chemical signature found in the remains.

In the 11th century, the Persian scholar Abu Rayhan Biruni described a recipe for crucible steel in his work al-Jamahir fi Marifah al-Jawahir. The recipe lists ingredients measured in units of ratl and dirham, including a substance called “rusakhtaj”.

For centuries, the identity of rusakhtaj was unclear. Researchers now argue that it likely refers to chromite.

In Biruni’s account, iron objects such as horseshoes and nails are placed in a crucible along with measured quantities of minerals. The vessel is sealed with clay and heated in a charcoal furnace using bellows operated by two men until the iron melts. After sustained firing, the crucible is left to cool and a steel ingot is removed.

Some aspects of the description are difficult to interpret. Medieval technical texts often omit practical steps or use terminology that no longer has an exact modern equivalent. But the presence of a mineral additive in the written recipe, combined with the chromium detected in excavated production waste, strengthens the case for deliberate alloying.

The Chahak crucibles themselves were built to withstand extreme heat. Reconstructed from fragments, they appear cylindrical, roughly 27 centimeters high without the lid, with thick, refractory walls containing more than 25 per cent alumina.

Textile impressions preserved on the inner surfaces suggest the clay was shaped by hand, possibly using fabric to help draw the walls upward. The vessels were sealed during firing, allowing the iron inside to melt without direct contact with the furnace atmosphere.

Most surviving crucible steel artefacts from the Islamic world are weapons — swords, daggers and armor — often associated with patterned “Damascus” surfaces. Many lack clear information about where they were made. Chemical composition can sometimes link objects to production centers.

One such object, a medieval Islamic flint striker in the Tanavoli Collection, had previously been analyzed and found to contain more than one percent chromium. At the time, there was no confirmed production site known to have made chromium-bearing crucible steel. The material from Chahak provides a plausible origin.

Historical sources from the 13th century onwards describe Chahak steel as visually fine but brittle. The new analyses show that, in addition to chromium, the steel contained relatively high levels of phosphorus.

Phosphorus can increase brittleness, particularly in high-carbon steels. The chemical profile matches the historical description.

The production debris also shows other distinctive features. Smithing slags from the site are unusually rich in lime and low in silica compared with crucible steel waste from Central Asia and South Asia.

The chromium signature appears in slag from the melting stage but not in later smithing slag, indicating that chromium was introduced during the crucible process rather than during forging.

Crucible steel traditions are known from Central Asia and from South Asia, where the product was called wootz. The Chahak material demonstrates that within the Persian tradition, at least one production centre was using a chromium-bearing mineral as a regular additive by the early second millennium CE.

The quantities involved were modest by modern standards. Around one per cent chromium does not produce stainless steel. But the addition was systematic. Multiple samples from different contexts within the site show comparable levels.

The findings depend on a combination of archaeological excavation, radiocarbon dating and microscopic chemical analysis using scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive spectroscopy.

Carbon content in the ancient iron could not be measured directly because samples were carbon-coated for analysis, but etching techniques confirmed high-carbon steel typical of crucible production.

Chahak is currently the only confirmed crucible steel production site identified within Iran’s present borders. Manuscripts from later medieval and early modern periods indicate that production continued beyond the Mongol invasion and into the Safavid era.

The evidence from Chahak shows that by the 11th century, Persian steelmakers were operating furnaces capable of melting iron, producing high-carbon steel ingots and incorporating chromium-bearing minerals into the charge in a controlled and repeatable way.

‘We will not bow to pressure or coercion’: President Pezeshkian

Trump raises global tariffs to 15%, calls Supreme Court ruling ‘ridiculous’

IRGC Navy tests Sayyad-3G air defense missile in Strait of Hormuz

Iran labels EU naval, air forces as ‘terrorist’ in response to IRGC listing

ICE quietly buys warehouses for major detention expansion

Family of US citizen killed by Israeli settler demands end to impunity

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

VIDEO | Trump’s 'Gaza Riviera' vs. tents: Deep divide over US' 12-point plan

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website