Diagnosing the roots of Iran’s economic turmoil

A recent televised discussion presented the economic strain of recent weeks as an extension of street unrest, arguing that “agitators” operate not only in public spaces but also within the economy.

The presenter called for decisive action against “economic agitators”, a position echoed by the guest, who had previously questioned whether rising prices reflected natural economic forces or a deliberate effort to manufacture public dissatisfaction.

The political economy that has emerged over years, particularly after the implementation of privatization policies under Article 44, has favored large quasi-state enterprises dependent on cheap energy and raw materials rather than innovation or technology.

Within this framework, networks of influence tied to these enterprises have gained prominence, shaping economic rents and national resource allocation.

In December 2025, the rial experienced a sharp depreciation against the dollar, with the open-market exchange rate reaching around 1.5 million rials per dollar.

The collapse in the currency’s value was followed by scattered protests by traders in several cities. These demonstrations were quickly appropriated by foreign-linked elements and escalated into violent unrest.

Iran faces a large fiscal deficit, deep stress within the banking and social security systems, a money supply measured in the tens of thousands of trillions of rials, and inflation approaching 50 percent.

These conditions exist within an economic structure characterized by heavy reliance on oil revenues. The economy expands rapidly during periods of high oil prices and export volumes and contracts sharply when those revenues decline.

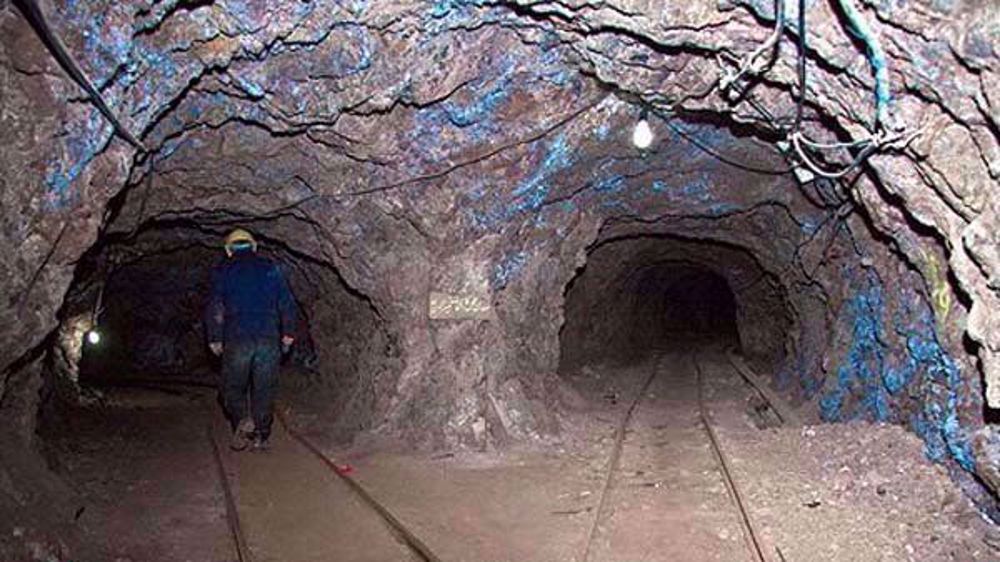

Iran was among the first countries in the region to discover oil at the start of the twentieth century and later became the world’s third-largest holder of proven oil reserves.

In 1909, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was established with extensive exploration and production concessions, and the British government later acquired a majority stake, securing direct influence over Iran’s oil resources.

A decision by Winston Churchill, then Britain’s first lord of the admiralty, to shift the navy’s fuel from coal to oil elevated Iranian oil to strategic importance and tied the economy early on to western markets and geopolitical calculations.

In subsequent decades, oil remained central but did not produce broad-based industrialization. A significant share of revenues flowed abroad, while the domestic economy remained heavily dependent on traditional agriculture, with only limited growth in processing industries.

This imbalance peaked with the nationalization of oil under prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh, before ending in 1953 with his removal and the return of the Shah, reinforcing alignment with the West and concentrating political and economic decision-making within the monarchy.

Rising oil prices in the 1960s and 1970s drove rapid economic growth. Urban areas expanded, but growth was uneven. Wealth became concentrated among limited groups and major urban centers, while rural areas and urban peripheries experienced deprivation and marginalization.

The absence of political participation and continued repression eroded the regime’s legitimacy by the late 1970s, contributing to widespread public anger and the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979.

After the revolution, a new economic model emerged, centered on nationalization, price controls and extensive subsidies for basic goods. These measures were designed to support lower-income groups and reinforce the economic and institutional infrastructure.

From the outset, this model operated under intense political strain and expanding sanctions.

Iran has experienced some of the longest and most extensive sanctions regimes globally. Although adaptation mechanisms developed over time, sanctions affected all sectors of the economy and daily life.

Following the US embassy takeover in Tehran, the Carter administration froze Iranian assets worth an estimated $9 billion to $12 billon at a time when Iran’s GDP was about $90 billion and cut trade ties, including oil purchases. The impact was immediate in an economy that had been relatively open to global trade.

Less than a year later, Iraq invaded Iran, triggering an eight-year war. Oil exports fell, government revenues declined and military spending surged, while infrastructure, particularly in border and oil-producing regions, sustained heavy damage.

Resources were diverted to the war effort, limiting investment and development. Restricted access to foreign finance and technology slowed economic activity and contributed to inflation and shortages.

After the war ended in 1988, the focus shifted to reconstruction, with efforts to revive productive sectors and stimulate investment, especially in industry, energy and infrastructure.

World Bank data show that economic performance improved in the early 1990s, with growth rates of 4 to 6 percent and an increase in the share of manufacturing in GDP from about 14–15 percent in the late 1980s to around 18–20 percent by the mid-1990s.

During this period, US sanctions gradually expanded. Secondary sanctions, extending penalties to third countries trading with Iran, intensified the pressure.

Beginning in the 1990s, restrictions were placed on foreign investment in Iran’s energy sector, forcing many international companies to choose between the Iranian and US markets.

Sanctions also constrained Iran’s ability to develop its vast gas reserves, despite holding the world’s second-largest reserves.

Major gas field discoveries and development in the 1990s occurred amid restrictions on foreign investment and technology transfer, limiting expansion and confining gas use largely to the domestic market.

By 2010, secondary sanctions became broader and more severe, directly targeting banking and trade finance. Engagement with Iran became high risk for banks and companies in Europe and Asia due to potential loss of access to the US financial system.

Escalating pretexts over Iran’s civilian nuclear program led to European and UN sanctions. By 2012, oil exports to Europe were banned and Iranian banks were cut off from the Swift payment system, sharply reducing foreign currency inflows and accelerating the rial’s depreciation.

The currency shock fed directly into prices, pushing inflation above 30 percent in subsequent years in an import-dependent economy.

The government expanded subsidies and financed budget deficits through the central bank, easing pressures temporarily while entrenching structural imbalances and chronic inflation.

The period marked the onset of prolonged stagflation, eroding low-income households and the middle class through depleted savings and lack of sustained improvement.

Climate pressures, particularly drought and water scarcity, compounded economic stress by damaging agriculture and increasing livelihood vulnerability. Fuel subsidies kept gasoline and diesel prices among the lowest globally, encouraging smuggling to neighboring countries and draining public resources.

Multiple exchange rates were used to supply subsidized dollars for essential imports, creating arbitrage opportunities for those with access while most consumers faced market rates.

The interaction of sanctions, currency controls and trade restrictions fostered networks able to exploit price gaps and shortages through informal import and financing channels.

While food and medicine were formally exempt from sanctions, financial constraints disrupted payments, leading to shortages and rising costs, including for cancer and chronic disease treatments. Aviation safety was also affected by restrictions on aircraft purchases and spare parts.

From 2024, the government of Masoud Pezeshkian introduced limited economic reforms, including subsidy adjustments and price oversight, amid questions over their effectiveness in containing inflation and improving living standards.

Any serious attempt at reform directly threatens the extensive interests embedded among powerful layers of “economic agitators.”

Under conditions of mounting social pressure and declining public approval of the government, confronting these groups carries the potential to generate major challenges.

In other words, the issue is not limited to the lifting of sanctions alone, but requires deep structural reforms, the implementation of which necessitates painful economic decisions.

On this basis, a major change is taking shape, the success of which depends on internal cooperation and cohesion.

This point was underscored on Friday by Leader of the Islamic Revolution Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei who emphasized that the president himself, along with the heads of the other branches of government, should be allowed to carry out their work and the heavy responsibilities entrusted to them.

Why Global Majority must unite against US imperialism in Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, Gaza

Iran warns of environmental impacts of US-Israeli war, calls for swift UN action

‘Just getting started’: Iran blasts Israeli censorship of punishing blows

Iraqi Islamic Resistance says 13 US soldiers killed in 291 operations

'Heinous crime’: Iran denounces Israeli assassination of 4 Iranian diplomats in Lebanon

IRGC announces launching multiple new waves of Operation True Promise 4

Pakistan felicitates Ayatollah Mojtaba Khamenei on election as Iran's new Leader

FM: Trump's claim that US averted 'preemptive' Iranian strike 'utter lie'

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website