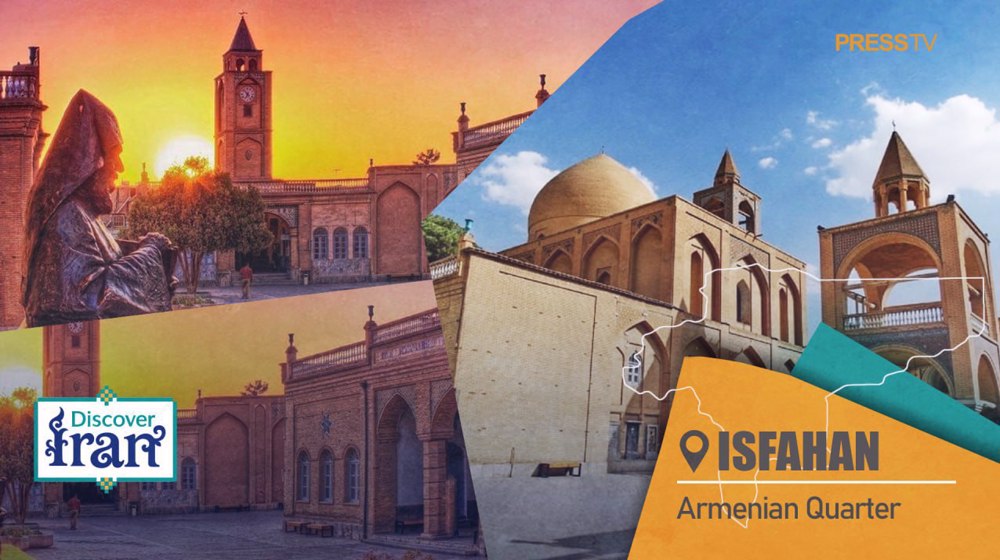

Discover Iran: New Julfa, Isfahan’s Armenian quarter that blends faith, trade and culture

By Maryam Qarehgozlou

- Founded in 1606, New Julfa in Isfahan city became a thriving Armenian quarter, blending Persian traditions, Christian faith, and flourishing trade.

- Armenian merchants connected Isfahan to global commerce, exporting silk and importing silver, spices, and luxury goods across continents.

- Vank Cathedral and numerous churches symbolize cultural coexistence, preserving Armenian heritage while reflecting Safavid artistry and religious tolerance.

New Julfa, the Armenian quarter of central Iran’s Isfahan province, founded in the 17th century, stands as a vivid reminder of cultural exchange, religious tolerance, and artistic brilliance.

Narrow lanes lined with ochre-brick houses, carved wooden balconies, and quiet courtyards invite you deeper into a district that feels like a world of its own.

New Julfa is a place born from exile, but it blossomed into one of the most dazzling stories of cultural coexistence and global commerce in early modern history.

The story of New Julfa begins in 1606, when Safavid ruler Shah Abbas I ordered thousands of Armenian families from the town of Old Julfa on the Aras River to relocate to his new capital.

At first glance, it appeared as displacement, but Shah Abbas’ move served a dual purpose: shielding the Armenians from Ottoman expansion while strategically strengthening the Safavid state.

Armenians were known as skilled merchants, artisans, and diplomats. By relocating them to the newly created suburb of New Julfa, south of the ZayandehRud River, the Safavid state tapped into their international networks that stretched from Amsterdam to Calcutta, Manila, and Venice.

Armenian merchants played a central role in the silk trade, acting as intermediaries between the Safavid Empire and European powers, bypassing Ottoman middlemen and placing Isfahan directly into the arteries of world commerce.

They exported Persian silk to European markets and brought back silver, spices, and luxury goods.

Within decades, New Julfa became one of the most prosperous trading hubs in Asia, linking Iran to global commerce.

Their role went beyond commerce—Armenian envoys often represented the Safavid ruler at foreign courts, highlighting their importance as cultural and political bridges.

The wealth they accumulated found expression back home — in houses with hidden gardens, in libraries filled with manuscripts, and most enduringly, in the walls and domes of their churches.

The most famous is Vank Cathedral, completed in the mid-17th century. Unlike traditional Persian mosques, its design blends Armenian Christian traditions with Safavid architectural styles.

Its plain exterior conceals richly painted frescoes inside, depicting biblical scenes alongside motifs inspired by Persian miniature art.

The cathedral’s museum preserves rare manuscripts, chalices, vestments, ancient Bibles, and documents that testify to centuries of Armenian presence in Iran.

Visitors also encounter one of Iran’s oldest printing presses, brought to New Julfa in 1636, which began a new era of publishing in the country.

The Armenian Genocide Memorial, located within the Vank Cathedral complex, built in the 1970s, commemorates the victims of the 1915 massacres during the Ottoman Empire.

Alongside Vank, more than a dozen other churches were built in New Julfa, each carrying layers of memory and artistry — St. Mary’s with its delicate paintings, St. George’s with relics brought from Armenia, Bethlehem with its cycle of 72 luminous frescoes.

This religious freedom was exceptional for the time. Armenians, while Christian in a Muslim-majority country, were allowed to practice their faith openly and maintain their institutions. Their coexistence with Muslim neighbors in Isfahan was totally peaceful, and that continues to this day.

For Muslim Isfahanis, the quarter became a living reminder that their city was a crossroads of civilizations, where the call to prayer and the peal of church bells mingled without discord.

Let's take a brief look at Isfahan — a historic city where Iran’s ancient glory meets modern industry. From breathtaking architecture to thriving modern factories discover why Isfahan is truly half the world.

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) September 13, 2025

Follow Press TV on Telegram: https://t.co/LWoNSpkc2J pic.twitter.com/iMxfwd5tvA

Although many Armenians emigrated after the 20th century, the neighborhood retains an active Armenian presence, and New Julfa remains one of the strongest Armenian cultural centers in West Asia.

Beyond its historic landmarks, New Julfa has in recent years become known for its cafes and restaurants, many of which are tucked into renovated old houses.

Cobbled lanes lead to cafes where the scent of Armenian coffee fills the air, and to shops selling silver crosses, carpets, and miniature paintings.

These spaces attract both locals and tourists, offering a contemporary social scene alongside centuries-old architecture.

Muslim and Armenian residents continue to share the same urban space, with Armenians maintaining schools, libraries, and cultural associations.

Festivals such as Christmas and Easter are still celebrated with great fervor publicly, with Muslim neighbors joining in a beautiful display of camaraderie and togetherness.

New Julfa’s trade history, churches, museums, and everyday life highlight how people carved out prosperity and preserved their identity, which is evident today.

Pezeshkian: Nakhchivan aerial bombardment not linked to Iran

US, Israeli targets struck in mass IRGC missile, drone strikes

Supporting anti-Iran aggression constitutes complicity in war: Pezeshkian tells Macron

Iran Parliament hails election of new Leader, pledges allegiance

Iran's defense and security institutions unite in steadfast allegiance to new Leader

Profile: Ayatollah Seyyed Mojtaba Khamenei, third Leader of the Islamic Revolution

Resistance groups congratulate Iran on Ayatollah Mojtaba Khamenei’s election as new Leader

Triumphant unity: Top Iranian officials rally behind new Leader of Islamic Revolution

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website